With their high-vis yellow jackets and red helmets, it's not hard to find members of the Sauvetage Bénévole Ottawa - Ottawa Volunteer Search and Rescue. But they'll probably find you first.

Thud … thud … thud.

The sound was unmistakable to the handful of volunteer searchers combing through the rugged bush near Low, Que. A father and son, Paul and Patrick, went missing overnight in the wilderness. Now someone was responding to the searchers’ whistles — pounding a tree with a branch, perhaps. Three signals: the universal distress call.

Sign up to receive daily headline news from Ottawa Citizen, a division of Postmedia Network Inc.

Thanks for signing up!

A welcome email is on its way. If you don't see it, please check your junk folder.

The next issue of Ottawa Citizen Headline News will soon be in your inbox.

One of the searchers, Julena Breel, held a compass bearing toward the direction of the sound as team leader Kate Van started to count: “One, two, three…

“PAUL!” the team shouted in unison.

A muffled “Hello” wafted out from the forest.

“One, two, three…” Van began again.

“STAY PUT!” the group shouted. Then the five members of “Foxtrot”, one of seven ground search parties looking for the missing hikers, headed single file into the bush, following the base of a snow-covered ridge.

With their high-vis yellow jackets, red helmets and crackling radios, it’s not hard to find members of the Sauvetage Bénévole Ottawa – Ottawa Volunteer Search and Rescue.

But they’ll probably find you first.

Formed in 1996, SBO-OVSAR could use a smaller acronym, but they’ve been too busy growing into the largest volunteer search and rescue team in Canada. At a moment’s notice, the group of teachers, public servants, students, tech workers, and retirees will put their lives on hold, grab “go-bags” of outdoor gear and head out to a call that can be anywhere in Eastern Ontario or Western Quebec.

And they are increasingly called upon for help, often by the police, like when OPP needed their assistance last year in tracking down a three-year-old boy lost in the bush near Westport.

SBO-OVSAR’s reputation has grown to the point that municipalities will call to enlist its skills in emergency situations. The group was sandbagging in Constance Bay during the record Ottawa River flood in 2017, searching through debris in Dunrobin after the 2018 tornado, and assisting Ottawa Public Health at a mass COVID-19 vaccination clinic at the Canadian Tire Centre.

“There’s a camaraderie in the group that’s really special,” said Catherine Dumouchel, who joined the search and rescue group 15 years ago and is now director of its incident management team. She first came upon the group while out for a hike with her spouse in Gatineau Park, where she saw SBO-OVSAR in action. “We got really interested and thought, ‘What a wonderful way to give back.’ To combine our love of the outdoors and to provide a meaningful contribution to the community, this was just the perfect outlet.”

Urbanites might have spotted the team this fall when they canvassed at stores like Sail and MEC, this time in search of public support for an online campaign to win the Land Rover Defender Service Award. SBO-OVSAR bested nearly 900 search-and-rescue teams from across North America to win a rugged offroad vehicle, the Defender, which they will accept in the new year.

“That really helped raise our public image and it was a real morale boost for the team,” said Steve Nason, director of operations.

An adventure racer, Nason joined the team to learn more about back-country navigation. He was quickly hooked by search and rescue.

The team counts about 150 members and does two intakes in the spring and the fall of about 25 recruits each. Volunteers pay for their own training and outdoor gear. (The jackets alone cost $600.) Tuitions help finance the operation, which is self-funded.

The training culminates in a sophisticated and realistic training exercise—like the hikers in Low who went “missing.”

On a snowy Saturday morning in November, team members begin to arrive at the search site at a Scout camp, 50 kilometres north of Ottawa.

While search leaders set up in a mobile command trailer, volunteers ready their gear, lace up hiking boots, check GPS batteries and stuff energy bars into their pockets. Some carry radios — the area is outside cellphone coverage — while others strap red first aid kids or climbing ropes to their backpacks.

A drone team flies their craft overhead, its infrared camera revealing ghostly white heat images of the searchers below. Another team on fat-tired bikes prepares to search trails and bush roads.

There is a science to searching and Robert Koester is the author of their bible, Lost Person Behaviour. An outdoorsman and former Eagle Scout from Virginia, Koestler has amassed data from more than 183,000 searches in the International Search and Rescue Incident Database.

“People behave differently depending on the situation,” Nason said.

Most forests are crisscrossed by animal paths that make natural trails people will follow. But someone with autism, for example, might travel in unexpected ways, attracted to water or lights.

“There was a search in the United States where a boy with autism went straight up a steep hill because he could see a light shining on a tower,” Nason said. “Most people wouldn’t have even tried to climb up a hill like that, but he wanted to get to the light.”

A person with dementia, meanwhile, may think they’re headed to a specific place so will often travel in a straight line, regardless of the terrain or obstacles in their path. An experienced hiker might parallel a stream or be lured into following a logging road, which may go nowhere. Someone who’s in mental distress or suicidal may be heading toward a favourite location in the woods.

Once Jack Ricou, the incident commander for SBO-OVSAR’s exercise, briefs the searchers on the father-son duo they are looking for, the volunteers break up into groups. The teams are equally divided based on skills like radio use, wilderness first aid training, and navigation expertise. Search planners dispatch the teams with instructions on where and how to search, labelling each with an identifier from the phonetic alphabet.

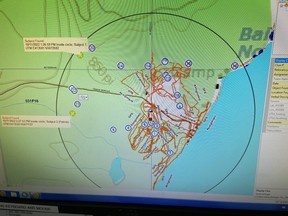

Kate Van and Team Foxtrot are assigned to sweep an area of bush not far from the command post. They spread out in a line at 10-metre intervals and advance into the trees, carefully noting the GPS coordinates to radio the information back to the command post. The computer at the command post with a map of the search area is soon covered in a spiderweb of red lines.

Every so often the searchers stop and blow their whistles in unison, then listen silently for a response. It’s late afternoon when Foxtrot hears the triple thud from the woods.

Within minutes they’ve found the first hiker, “Paul”, the father. He’s been there since before sunrise, bundled against the cold but feigning a broken leg.

Foxtrot’s Pierluc Seguin, a trained first aider, assesses the injury and comforts the victim, who deals the searchers a surprise: there’s a third hiker missing. They picked up a friend of Paul’s son on their drive out of the city, but Paul and his son got into a heated argument and the two teens headed off on their own. Alone, Paul fell on a slope, breaking his leg.

Foxtrot’s radio operator reports the new information to the command centre. The other teams get briefed and the search is expanded.

With meticulous care, Paul is wrapped in sleeping bags for warmth and strapped in tight on a collapsible stretcher. A team of six carries him out of the bush to a waiting all-terrain vehicle.

It isn’t long until the missing boys are found. This exercise is a success, but real callouts don’t always have happy endings. Sometimes the search is for crime scene evidence. Sometimes what they find is a body.

“We’re often seeing people on the worst day of their lives,” Dumouchel concedes.

Fortunately, most searches are successful. Few are more rewarding than the March 2021 search for three-year-old Jude Leyton, the boy who went missing near Westport. The OPP called for help, and SBO-OVSAR was able to consistently provide a team of 20 or 30 searchers each day.

Three days passed and hope began to fade. “It was right near a lake,” Nason said. “In the back of your mind, you’re thinking ‘He’s gone through the ice.'”

But the searchers never gave up. Then, almost four days after Jude went missing, an OPP officer spotted the boy’s blue jacket. Jude was found safe and remarkably healthy.

“Jude was returned to us due to the unrelenting dedication and perseverance of the OPP’s Search and Rescue Ground, Air, and Underwater teams and tireless effort of community volunteer searchers, firefighters and paramedics,” Jude’s mother, Katherine, said in a statement.

“We can’t begin to express how we feel to have our incredible, resilient son Jude back safe in our arms.”

It’s successes like this that keep Ottawa’s search and rescue volunteers picking up their phones in the dead of the night, trudging out into the winter chill to answer the call.

To find out more or to get involved with Sauvetage Bénévole Ottawa-Ottawa Volunteer Search and Rescue visits its website at sbo-ovsar.ca

-

'You don't lose hope': How a lost little boy was found

-

Missing boy in South Frontenac found alive