Drug-alternative machines use palm prints to verify users' identity

The professionals behind Vancouver’s drug-vending machines acknowledge it is possible that patients have sold or handed out their prescriptions to youth on the streets.

But the organization and its supporters say it’s important to keep in mind what these machines are intended to do — prevent British Columbians from dying from tainted, illicit opioids.

Start your day with a roundup of B.C.-focused news and opinion delivered straight to your inbox at 7 a.m., Monday to Friday.

Thanks for signing up!

A welcome email is on its way. If you don't see it, please check your junk folder.

The next issue of Sunrise presented by Vancouver Sun will soon be in your inbox.

“We need to ask ourselves the bigger picture here and acknowledge why and what youth are doing to not die from the toxic drug supply,” MySafe said in a statement. “It is becoming clearer that young people need support and safer access, too.”

Last week, Global News reported claims from the director of a New Westminster recovery centre that youth were taking transit downtown to get their hands on MySafe’s prescription hydromorphone.

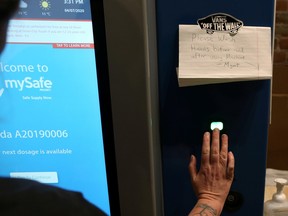

First installed as part of a 2019 pilot program, three vending machines dole out daily doses of the pharmaceutical alternative to Vancouver patients, who the machines identify using a biometric scan of the vein patterns in their palms.

A fourth MySafe machine in Victoria serves 30 people.

Jessica Cooksey with Last Door Recovery Centre — which relies on peer support and group exercises to rehabilitate clients struggling with substance use — said she knows of youth who are purchasing the pills.

“Youth and emerging adults are accessing these prescriptions,” said Cooksey, who was unwilling to provide any more details on where or from whom she heard the claims.

In a statement, a MySafe spokesperson said, “we cannot say 100 per cent that there has never been diversion to another person … from what we have observed, any diversion is to a friend or partner who is drug sick.”

When asked about the matter during a press conference last week, B.C. Premier, David Eby said “in terms about diversion or access of youth to drugs, this is a profound concern.”

The B.C. Liberal mental health and addictions critic, Elenore Sturko, criticized the premier. She said the province’s safer-drug-supply rollout needs stricter management.

“There needs to be oversight so that whenever any addictive drugs that are being publicly funded and supplied, there are also adequate safety measures in place to make sure they’re going to the right people.”

Sturko said that since calling for new government measures to stop the illegal diversion of MySafe prescriptions, she received some backlash.

“Advocates for getting free drugs are mad,” Sturko said. “A drug dealer doesn’t have to care where their drugs go. But when the government of British Columbia and Canada are supplying drugs to people, the public needs to know what’s happening there.”

Since B.C. began rolling out safer-supply programs in spring 2020, more than 10,000 citizens have been prescribed opioids through a handful of federally approved and funded programs. All require a prescription from a doctor or nurse-practitioner.

Those who stand behind B.C.’s supply — and its part in damming the rising tide of overdose deaths — continue to sing the praises of programs like MySafe.

Addictions interventionist Andrew Bhatti says most of the parents he works for “would rather have their kid buy safe supply than street drugs, which could kill them.”

Bhatti, who spent six years living on the Downtown Eastside streets struggling with a substance use disorder, says the diversion of prescription narcotics is nothing new.

“People have been selling their methadone prescriptions since we first knew about it 1993 … when I was dope sick, I used to buy people’s morphine pills.”

He said people who sold him the prescriptions would use the cash to buy other drugs or food.

As well as connecting patients to rehabilitation treatment, health professionals who oversee MySafe carry out regular urine tests in an effort to reduce the diversion of prescriptions.

“We always find Dilaudid (hydromorphone) in the samples. On two occasions we have not, we spoke with the participant to assess whether continuing with the program was right for them,” said the organization.

Latest statistics show nearly six residents are dying each day from B.C.’s illicit drug supply, which is often poisoned by dangerous added drugs, primarily fentanyl.

The hydromorphone that MySafe dispenses accounts for less than five per cent of all its prescriptions in Vancouver. The majority is distributed directly by pharmacies.

Ottawa announced in 2021 that it is funding the $3.5 million expansion of MySafe to two more Canadian cities — Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, and London, Ontario.

— With files from Katie DeRosa

sgrochowski@postmedia.com

twitter.com/sarahgrochowski

Support our journalism: Our in-depth journalism is possible thanks to the support of our subscribers. For just $3.50 per week, you can get unlimited, ad-lite access to The Vancouver Sun, The Province, National Post and 13 other Canadian news sites. Support us by subscribing today: The Vancouver Sun | The Province.

-

Measuring success: There's no agreement on how to decide whether drug decriminalization works

-

Death of Victoria man at 844 Johnson: 'We both knew this building was going to kill him'