Psychiatric patients were even more isolated than those in long-term care during the pandemic, says the mother of Michael Thomas. 'I felt he was in this asylum, and we couldn’t help him.'

CONTENT WARNING: This article mentions topics related to suicide.

A grieving Ottawa couple has asked the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario to review the medical file of their son who died by suicide last year at The Royal.

Sign up to receive daily headline news from Ottawa Citizen, a division of Postmedia Network Inc.

Thanks for signing up!

A welcome email is on its way. If you don't see it, please check your junk folder.

The next issue of Ottawa Citizen Headline News will soon be in your inbox.

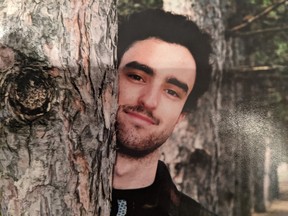

Michael Thomas, 28, died in his room on July 1, 2021 by inhaling helium, a lighter-than-air gas. Helium displaces oxygen and can cause asphyxiation.

An inpatient in the schizophrenia unit at The Royal Mental Health Centre, Michael’s death came more than one year into the COVID-19 pandemic.

Restrictions imposed by the hospital significantly worsened Michael’s mental health, his parents say. During the pandemic, Michael was unable to accept visits from his naturopath or massage therapist; his parents were only able to see him at a distance.

“We couldn’t understand the logic of this hospital policy knowing the importance of providing contact and compassion, and how essential they are to mental well-being,” said David Thomas, Michael’s father. “We couldn’t even wave to him through the windows. It was complete isolation.”

Michael’s mother said psychiatric patients were even more isolated than those in long-term care during the pandemic. “I felt he was in this asylum, and we couldn’t help him,” said Judy Thomas.

Among other things, the Thomases want the college to review the way The Royal managed patients during the pandemic, and to issue a ban on helium balloons.

The inert gas is a common topic of discussion on internet suicide forums.

Helium should never have been allowed inside her son’s room, said Michael’s mother, who contends the hospital’s approach is particularly hard to understand given that her son had attempted suicide previously as an inpatient.

A spokesperson for The Royal said the hospital can’t comment on the specifics of the Thomas case “for privacy reasons.”

Karen Monaghan, the Royal’s director of communications, said all critical incidents undergo an internal review to understand if processes have to be changed to better protect patients, families or staff. Monaghan would not reveal what, if any, changes were made following Michael’s suicide or whether helium has been banned from the facility.

The Royal, she noted, provides care to people suffering from the most severe and difficult to treat mental health conditions. “Our condolences go to the family, friends and caregivers involved, not only in this case, but to all of those lost to suicide,” Monaghan said.

The Thomases said their son was a kind and compassionate young man with a zest for life. “He was a beautiful soul,” said David Thomas.

Michael grew up in Dunrobin. He loved sports – wakeboarding, cycling and swimming – and was a talented snowboarder and water polo player. He was also adventurous, and once travelled to India for a yoga certification.

He used yoga to treat persistent concussion symptoms. Michael suffered a series of concussions in his youth from taekwondo, skateboarding, snowboarding (he hit a tree) and competitive water polo. He played goalie on the Ottawa Titans water polo team and was regularly struck in the head by the ball.

His parents say they can’t distinguish now between the onset of his schizophrenia and his concussion symptoms, which included nausea, fatigue, insomnia and headaches.

Despite his health issues, Michael studied business at Bishop’s University where he was elected to the students’ association as vice president (social). He was also an advocate for mental health awareness and launched a pet therapy program for students struggling during exam periods.

His mental health took a dramatic turn for the worse in December 2016 when he became convinced he was being threatened by the mafia. His parents called a crisis line. They also called a police officer and a social worker, both of whom said Michael did not require hospitalization.

He intentionally overdosed on prescription drugs the following day and was rushed to Queensway Carleton Hospital. Michael stayed there until transferred to The Royal in May 2017.

He would never live outside a hospital again.

Michael spent almost a year in the schizophrenia inpatient program, trying different medications, before moving to the recovery unit in April 2018.

While in that unit, which is designed to prepare patients to be released from hospital, Michael organized a fundraising event called ‘Love Your Brain.’ It focused on concussion awareness, and featured four speakers and a question-and-answer session. The event concluded with Michael leading a yoga session for those suffering concussion symptoms.

The Thomases were thrilled with the evening’s success – it raised more than $2,000 – since it highlighted their son’s enormous potential. But in the spring of 2019, Michael’s condition deteriorated sharply.

He did not have a good relationship with his inpatient psychologist at the time, the Thomases said, and they asked the hospital if they could bring an outside psychologist at their own expense to work with Michael. The hospital said the proposal contravened its policy.

Michael was also beginning to skip some of his prescribed doses of Clozapine, an antipsychotic medication.

Said David Thomas: “We were concerned about the state of Michael’s mental health and were desperately trying to gain a better understanding of how best to support him.”

The complex question of capacity and consent made that difficult. In health care, individuals are allowed to make their own treatment decisions if they’re able to understand the relevant medical information and appreciate the consequences of their choices.

Adults are presumed to be capable and establishing a lack of capacity is not always straightforward, particularly in a setting like The Royal.

The hospital said Michael had the capacity to make his own decisions in the spring of 2019. Doctors told the Thomases to “be the parents” while staff took care of Michael’s psychiatric treatment.

“This is very different from a team approach,” David Thomas said.

According to his medical file, Michael became more withdrawn socially, lost weight, and shaved his head and beard.

The Thomases also discovered Michael was giving away some of his possessions, including a valuable snowboard – the kind of action considered a warning sign of suicidal ideation. They shared their concerns with doctors.

Michael’s medical file indicates he was placed on a heightened watch that summer, but he retained his privileges and was allowed to walk the hospital property freely, without supervision.

Meanwhile, plans for Michael’s departure from The Royal continued apace. He made more than 100 phone calls trying to find a place to live in the community – something that elevated his stress levels, his parents contend.

David Thomas did not believe his son was ready to live outside the hospital.

In September, a medical assessment concluded Michael was in decline, but categorized him as a “low imminent” safety risk. It recommended increasing his levels of Clozapine to address his anxiety and suicidal thoughts.

Another assessment in October said his change in presentation was concerning, particularly given his reduced use of Clozapine, but it also noted that any risk assessment was limited in Michael’s case by his reserve in discussions about self-harm.

The Thomases believe Michael’s hospital privileges should have been revoked until his medication had been adjusted.

On Oct. 20, 2019, as the Thomases were driving to Florida for an annual vacation, Michael left the hospital grounds and attempted suicide, the result of which left him with third-degree burns to more than 40 per cent of his body, a fractured vertebra, a punctured lung and other injuries. He was airlifted to Toronto’s Sunnybook Hospital burn unit.

The Thomases flew home to find their son in critical condition. They spent the next 10 weeks in Toronto as Michael underwent surgery, skin grafts and occupational therapy.

A capacity assessment conducted at Sunnybrook found Michael “unable to appreciate” proposed treatments. He was found incapable and his parents were made substitute decision-makers in November 2019.

Michael returned to the Royal in January 2020 and re-entered the schizophrenia unit. His Clozapine was restarted and he agreed to give his parents power of attorney.

But doctors said Michael was “withering.” Then, in March, the pandemic arrived. COVID-19 restrictions meant Michael lost the support of his naturopath and osteopath, Tom Tomlinson, who could no longer visit the hospital.

“He really had no place of peace,” says Tomlinson, who worked with Michael for about eight years. “I think I was one of the few people who could give him an hour or two hours of peace.” Tomlinson touched his physical wounds and taught him how to meditate. He would hold his head or shoulders during that process “just so that he could get out of himself, away from himself.”

When the pandemic hit, Tomlinson was able to correspond with Michael by phone and by email, but he was not allowed into the facility during lockdowns.

“I have no doubt in my mind it killed him,” Tomlinson says of the isolation. “He was calling for help, but nobody could give it to him…Even if I could have seen Michael in a hazmat suit, it would have been better because it’s that human contact that he needed.”

In a statement, The Royal said Thomas was the only inpatient to die by suicide in the past three years.

Monaghan said in-person visits have been permitted at the hospital since July 2020 with special protocols in place to guard against the spread of COVID-19 and other viral illnesses. Those restrictions, she said, are based on provincial guidelines and in line with those introduced at other health care facilities.

David Thomas says the ability to spend time with Michael during the last six months of his life “was almost nonexistent.” The Thomases would regularly deliver food to Michael, and sometimes the nurses would allow him to meet them at the main entrance for short visits. Other visits had to be held behind a Plexiglass shield, fully masked.

Michael developed a curious interest in helium balloons. He had used them as gifts for Mother’s Day and Father’s Day. The Thomases didn’t know what to make of the development. On June 30, 2021, they dropped off a bit of food for Michael and handed him several green balloons. Early the next morning, Michael died by suicide.

“Michael left a notebook that made for very sad reading,” his father said. “He felt he was alone, that the system had let him down and could no longer help him.”

SUICIDE WARNING SIGNS

Statements that reveal a desire to die

Sudden changes in behaviour: withdrawal, apathy, moodiness

Depression, crying, sleeplessness, hopelessness

Final arrangements such as giving away possessions

WHAT TO DO

Discuss it openly

Show interest and support

Get professional help

Call your local crisis line: