There is an abundance of beauty, sorrow and black humor in the artworks that make up “We No Longer Feel the Future,” a new exhibit of photos, paintings and sculptures by Ukrainian artists at the Eretz Israel Museum’s Migdal Gallery in Tel Aviv.

The exhibit is named for a work by one of the participating artists, Elena Subach, whose gripping photos and descriptions of Ukrainian women spark a deep and emotional reaction in viewers.

This was a last-minute exhibit in museum terms, an effort by Israeli curators Suzanne Landau and Svetlana Reingold, who wanted to “do something” amid the ongoing tragedy of the Ukrainian-Russian war.

“It was a very spontaneous reaction to what was happening,” said Landau, the longtime former Tel Aviv Museum of Art head curator. “When we were thinking about what we could do, our tools were an exhibit to show what they were doing.”

“Middle of the year requests are unusual,” said museum CEO Ami Katz during a press tour of the exhibit alongside head curator Debby Hershman.

Get The Times of Israel's Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories

“The budgets and calendar are already set. Debby said, ‘Nu, by the time the exhibit is ready the war will be over.’ And I said, ‘Debby, don’t worry.'”

One of the miniatures painted by Ukrainian-born Israeli painter Zoya Cherkassky, part of the ‘We No Longer Feel the Future’ exhibit that opened in November 2022 at the Eretz Israel Museum (Courtesy Zoya Cherkassky)

It was just a few months ago when Landau turned to Zoya Cherkassky, a well-known Israeli artist who immigrated to Israel from Kyiv, Ukraine, in 1981, asking her for names of Ukrainian artists.

Since February 24, when Russia invaded Ukraine, Cherkassky’s own bold oil paintings have focused on the personal and national tragedies taking place in Kyiv.

Cherkassky pointed Landau and Reingold in the direction of other Ukrainian artists who have been working in the months since the war began.

“Each one is a hero, continuing to do their work with modest means,” said Landau. “The world gets used to this situation but they’re living it. We just wanted to do this and to help these artists who are continuing to work even in war, because they feel that their art is their tool with which they can fight for their nation.”

From Ukrainian artist Elena Subach’s series, printed ink on paper, on exhibit at the ‘We No Longer Feel the Future’ exhibit that opened in November 2022 at the Eretz Israel Museum (Courtesy Elena Subach)

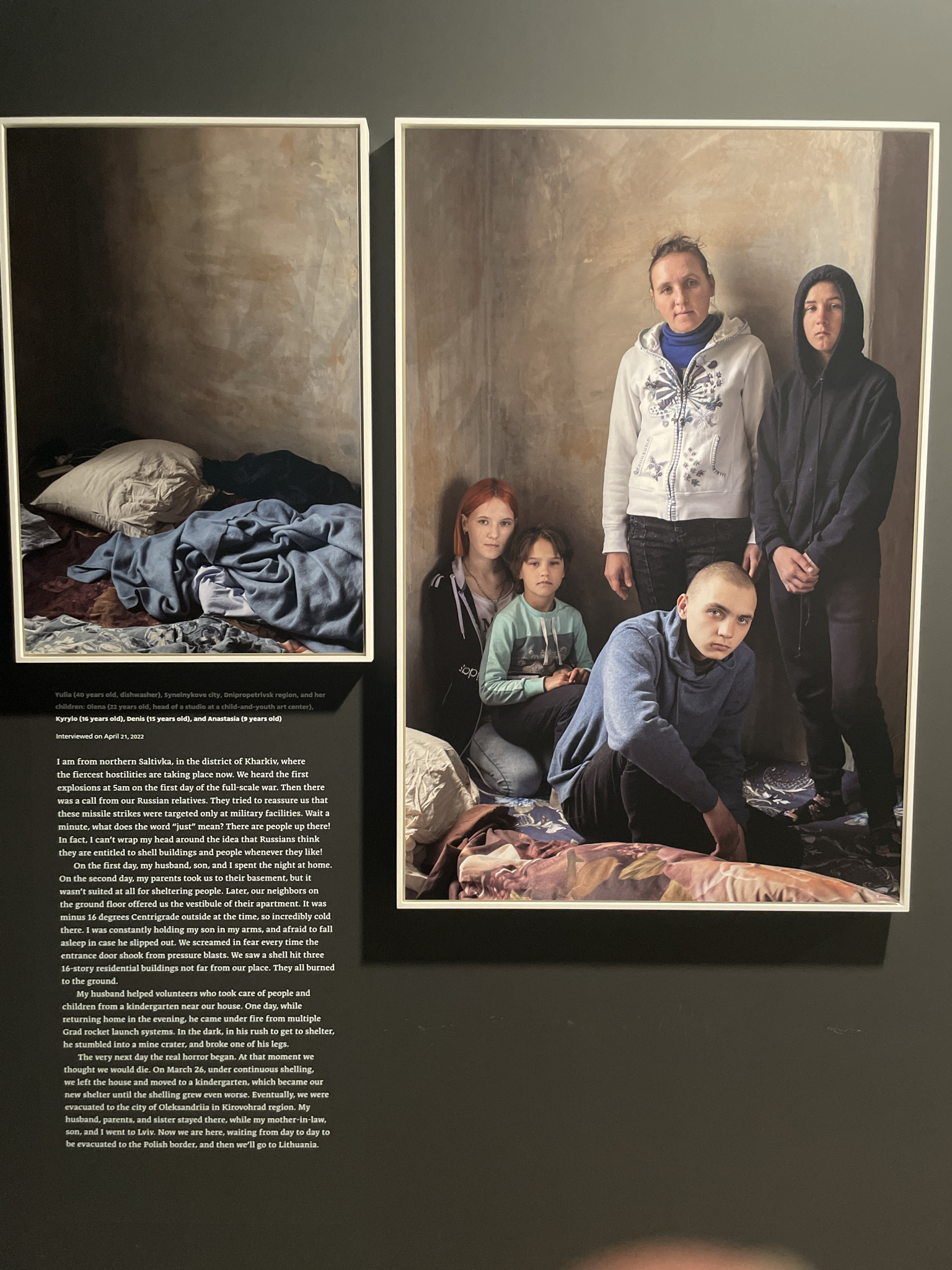

Subach’s photos are portraits of women and their families, part of a project she began working on a month after the Russian invasion of Ukraine began.

Subach’s goal is to portray and record stories of people who have been forced to leave their homes because of the war, with the photos taken in shelters for displaced persons in Lviv, where she lives.

Societal issues and feminism tend to be major topics for many of the women, said Landau.

Oksana Nevmerzhytska offers her series of photographs of hospital rooms empty of people, with tableaus of beds, tables and floor tiles of another era, in a building that appears abandoned by time.

There are two oversized portraits from a series by Lesia Khomenko painted on the flexible canvas of biflex, and Maryna Shtanko offers a pop-Soviet series of inkjet prints on paper, in which she layers elements of pop art onto photographs. Shtanko makes subtle and not-so-subtle references to the Russian-Ukrainian divide that’s become more obvious since 2014 invasion.

“We are so much alive, but still so different,” reads the cartoon balloon on a photo of two young women, one dressed in Soviet colors, the other in Ukrainian ones.

Maryna Shtanko’s Pop-Soviet series of inkjet prints on paper on exhibit at the ‘We No Longer Feel the Future’ exhibit that opened in November 2022 at the Eretz Israel Museum (Jessica Steinberg/Times of Israel)

Alevtina Kakhidze’s cartoonish images from the series “Wartime” point at oligarchs who have left Russia and renowned cultural figures, Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy and others, who represent a time that no longer exists.

Zoya Cherkassky’s 10 miniature paintings show graphic images of buildings burning, rockets flying and Ukrainians watching their cities be destroyed.

At the front of the gallery are the sliced river stones of Zhanna Kadyrova, part of “Palianytsia,” the name of her artwork that is also the term for a round Ukrainian bread that Russian occupiers cannot pronounce correctly and has become a password of sorts among Ukrainians.

Zhanna Kadyrova’s ‘Palianytsia’ collection of river stones sliced like bread, on exhibit at the ‘We No Longer Feel the Future’ exhibit that opened in November 2022 at the Eretz Israel Museum (Courtesy Zhanna Kadyrova)

A video shows Kadyrova in the process of creating her sculptures, gathered from a riverbed in the Carpathian Mountains, where she escaped to from Kyiv. The collection of gray and brown river stones are collected and sliced into “loaves,” and sales from the exhibition have raised more than 50,000 euros to buy essential supplies for troops and Ukrainians in need.

“We changed stone bread to real bread,” Kadyrova told The Art Newspaper during her popup exhibit of the sliced river stones at the Venice Biennale. “We did it because it was the only possible way for us to generate money without a studio and without our previous life. It wasn’t a philosophical thing. I needed to produce.”

Varvara Logyn’s brightly painted steel antitank obstacle replicas on exhibit at the ‘We No Longer Feel the Future’ exhibit that opened in November 2022 at the Eretz Israel Museum in Tel Aviv (Jessica Steinberg/Times of Israel)

Most of the artists’ works were already outside Ukraine, said Landau. Some were shipped to Israel from Germany and Belgium, while Kadyrova’s were sent from an Italian gallery.

Some pieces, however, were impossible to ship, such as Varvara Logyn’s brightly painted steel antitank obstacles, decorated with the detailed folk art style known as Petrykivka painting for the Ukrainian village where it originated.

Logyn has been decorating the steel X-shaped objectss around Kyiv using brushes made of cat and squirrel hair. She calls the painting process a kind of meditation that has helped her live with the ongoing war.

They couldn’t be shipped from Kyiv, said Landau, but no matter, “we have enough of those here,” she said. “We recreated what she did in Kyiv.”

The folk art is used to decorate the interior and exteriors of houses in Petrykivka, said Landau, as a kind of belief that the markings protect them from sadness and sorrow.