NEWYou can now listen to FoxNews articles.

My grandfather once told me the extreme cost of freedom and how important it is for Americans to look back on Independence Day. He sat on a deck overlooking a golf course where the sky blew red, white and blue fireworks. He was the paratrooper of the 82nd Airborne Forces during World War II, and when the national anthem was played, he ensured that we would stand and put our hands on our hearts, "Freedom is free. It's not. " He would have known that he lost his friend during the war.

At the time, I was too young to understand his point of view, but one day he was in Iraq with a rifle at a little girl in a yellow dress. I noticed that. She staggered near the alleys of the mosque, holding her arms full of weapons and heading for a distant smoke. As the plume rose, two of my teammates remained pinned by the fierce attack of the enemy and fought to reduce the overwhelming probability.

"You can shoot her," the voice next to me rang. "Technically".

American troops and veterans with PTSD have a chance to fight to heal

I had the girl's name, and everyone on my team,, but she was hanging out at our combat outpost. Most of the people at her outpost were interacting with her because she was all smiling, laughing, and cheering. During candy, hugs, and attention, she visited frequently to remind other soldiers to send their children home. In return for her gift we gave her, she chose her flowers for us, so we gave her the nickname "Flower Girl". She was so impressed with her gestures that I had a yellow daisy in the pouch of her chest rig for weeks.

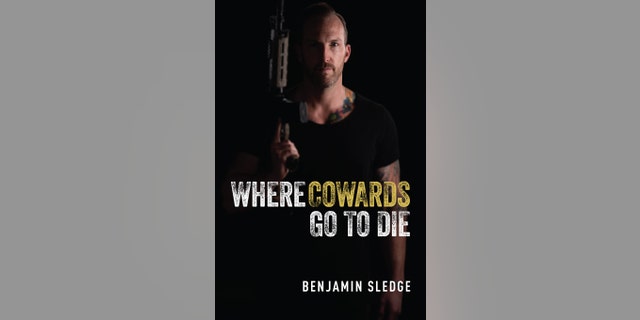

New issue of injured Iraq and Afghanistan veteran Benjamin Sledge "Where the coward dies."

When I looked into the scope, all my emotions shook and I stood paralyzed. What is your occupation. Am I the type of person who shoots children? Would you like to strengthen your enemies and sign your teammate's death certificate?

My fingers hovered over the trigger while other soldiers mysteriously turned to me. "They are doing this, you know. Use the kids to carry explosives and ammunition," he said.

Slowly, I lifted my finger from the trigger, off the edge, and handed over the rifle. I couldn't even look for the words, but he understood and struck my back and laughed.

"I had to see what type of man you were. We don't shoot children. We are American soldiers."

This was technically incorrect. I worked with a sniper named Stahvel to achieve an impressive number of kills. When talking one afternoon, he became solemn and told the night when the rebels tried to install multiple improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

"The first couple fell like a brick bag," Starbell said. Then he paused before speaking in a quiet tone. "Then this kid ran out of IED."

I already knew, so I didn't have to ask him to elaborate. During missions and patrols, Starbell and I had several conversations over the months, from hobbies to actions when we got home. Starbell loves golf and he planned to play a ton after he got home. He even played in some flashy tournaments as a scratch golfer. When he pulled the guard one afternoon, he made a statement that rocked my confidence in the efforts of the war.

"I played against a small number of Senators and Senatorson the golf course. They are all rich. The difference between me and them is that they war me. And I will trigger for them. "

A photo of Benjamin Sledge during the Iraq period.

His brutal honesty wasn't what I expected, so I ignored my responsibility and paid full attention to him. He continued to scan the horizon, looked into the scope, and then said over his shoulder.

When I got home, no one really knew about the harsh realities we face every day. While attending the funeral of the man I just talked about the day before, a politician visited and returned to a luxurious life. Then one day you will go home too. The experience is a little overwhelming. You are in Iraq or Afghanistan and a crowd is trying to kill you. Next you are at home and the crowd shouts, "It's the Pumpkin Spice Latte Season."

After returning from both Iraq and Afghanistan, the most obvious thing was that no one cares about the war because it didn't affect their lives. is. The war was background noise. The recent Cardassian scandal was even more noteworthy as dead soldiers in wooden boxes didn't go well with morning coffee.

A year after returning from Iraq, I woke up under a green, brown, and white striped duvet cover. The sun was shining through the window. Lying there in peace and tranquility, a deep awareness like a silent cancer spread to me. I joined the army in 1999 at the age of 18, but now 10 years ago,all I knew was war. I was training in the war, preparing to go to the war, or going on another development. Now the Army Reserves I joined have informed me that we are about to go abroad, and given my combat experience, they "needed" me.

Lying on the bed, I remembered a dozen men who knew they had been killed in action. Others died in suicide. There is no end to either of the current wars, so if you keep this tempo, you'll be in your thirties knowing only the war. Or maybe I will be killed. To make matters worse, I may finally snap and commit myself. Without a draft, it would always be the same man and woman returning abroad over and over again.

I ended the service shortly after the epiphany.

But even when he left the army, he never talked about war or the sacrifice of freedom. Civilians are uncomfortable when they look back at the moment of the "Band of Brothers" when people bleed, die, or explode their heads. They try to be polite, but we see it in the words of their bodies. It's a fake smile that says, "You're a monster." Most of the time, when we talk about the worst moments, we laugh to stay sane. The larger population is far from the moral dilemma we face in combat and our experience is alienated.

There is no community involvement or ownership in the dirty war business. Of course, it's in us because we heard the argument thatsoldiers "signed up to go", but it's lost its point and neglected responsibility. Since we live in democracy, we vote to leave it to men and women to govern our business, and elected representatives forget to send their troops abroad. We may have voted for someone else, but that doesn't change the fact that we were under US rule. When you live in a country, you are subject to its governing body and law without having to vote or agree. So the citizens of the house may not have triggered, but he asked the soldiers to go in his place.

Our war was different from my grandfather's. Looking back, Afghanistan and Iraq have become like Vietnam. Like a Vietnamese veteran, we no longer know what our goal was, but the price paid for over 20 years was astronomical. I know that our people who fought in the longest-running war in US history prevented other young men from being recruited. In the end, it sacrificed much of our life, our sanity, and our youth.

Click here to get the Opinion Newsletter

Of course, "Freedom is free Not. "" When I was that kid standing next to my grandfather, I bought a gingoistic, meaningless version of the phrase. Recently, I solemnly nod and understand the costs we often forget. Freedom always needs blood. The war has never been fought without men and women facing heartache, separation from the family, morally suspicious decisions, and death to keep the rest of the masses out of fear of combat. .. While sleeping in other parts of the United States, uniformed men and women die in each other's arms and are washed away with internal organs and tears.

But for us who fought.

Click here to get the Fox News app

Amazing cost for your neighbors I remember. Freedom purchased in our bloody sands, jungles, and mountains of land far from home.

For each Independence Day, we ask you to ponder the high cost of your freedom.

Benjamin Sledge is an injured combat veteran, touring Iraq and Afghanistan, most of the time under special operations (Civil and Psychological Operations Command). increase. He has been awarded the Bronze Star, Purple Heart, and two Army Awards for his actions abroad.Upon returning from the war, he began work on mental health and recovery from addiction. Part of this article is his bookWhere the coward dies