Chinese American Scholar Convicted of Spying for China

A federal jury in New York found Shujun Wang guilty of acting as a foreign agent for China. The pro-democracy activist turned spy gathered information on dissidents for over a decade.

A federal jury in New York has convicted Shujun Wang, a Chinese American scholar, of acting as an unregistered foreign agent for China. The verdict marks the culmination of a case that has exposed the complex world of international espionage and the challenges in identifying covert operatives.

Wang, who arrived in New York 30 years ago to pursue an academic career, helped establish the Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang Memorial Foundation, named after two reformist leaders of the Chinese Communist Party in the 1980s. This organization, based in Queens, was ostensibly dedicated to promoting democracy.

Prosecutors argued that Wang exploited his reputation as a pro-democracy activist to gather information on dissidents for China's Ministry of State Security, the country's primary intelligence agency established in 1983. For over a decade, Wang allegedly led a double life, gaining the trust of democracy advocates while secretly reporting their activities to Chinese authorities.

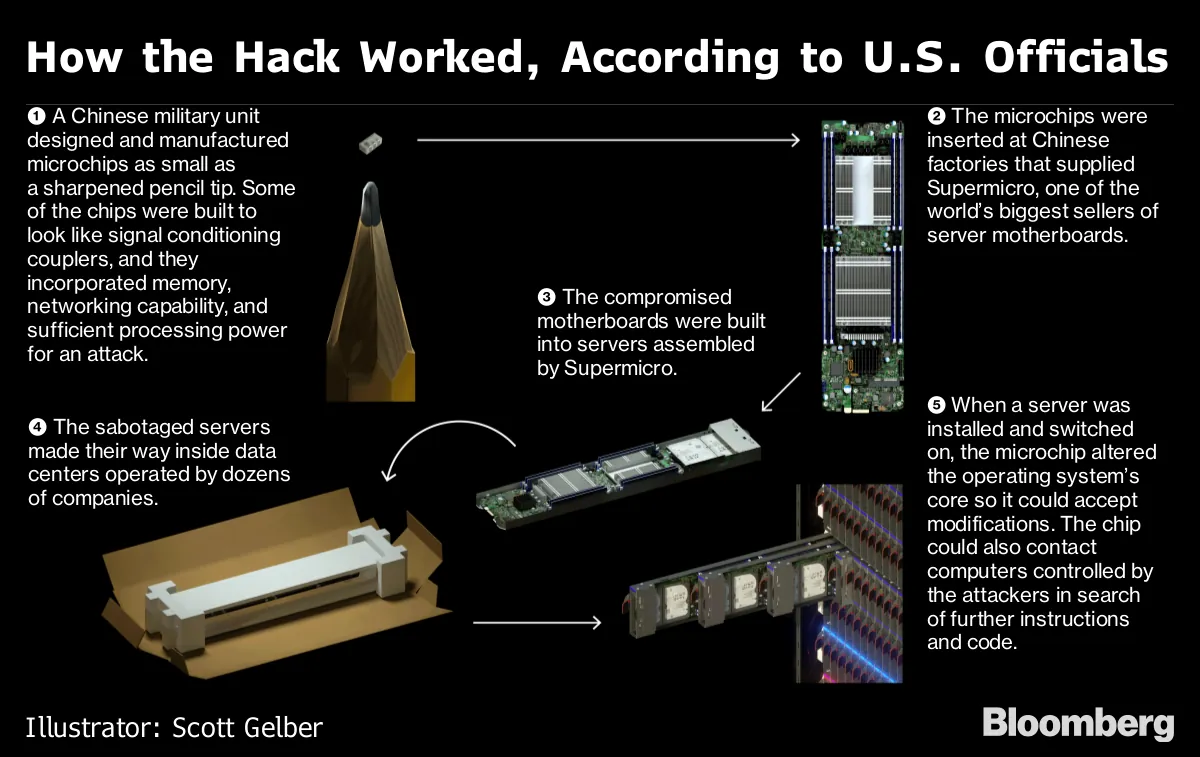

The prosecution detailed Wang's methods of communication with Chinese intelligence officers. He composed emails styled as "diaries," which contained information about conversations, meetings, and plans of various critics of the Chinese government. Instead of sending these emails, Wang saved them as drafts that could be accessed by Chinese agents using a shared password. This technique, known as "dead dropping" in intelligence circles, is a common method for covert communication.

Some of Wang's reports included details about events commemorating the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, which lasted from April 15 to June 4, 1989. He also provided information about planned demonstrations during visits by Chinese President Xi Jinping, who has held office since 2013.

FBI agents testified that during a series of interviews between 2017 and 2021, Wang initially denied any contact with the Ministry of State Security. However, he later acknowledged on video that the intelligence agency had requested him to gather information on democracy advocates.

"In general, fair to say he was very open and talkative with you, right?"

The defense portrayed Wang as a gregarious academic with nothing to hide, suggesting that his actions were misunderstood. They argued that the information Wang provided was already in the public domain and that he was merely engaging in academic discourse.

Despite these arguments, the jury found Wang guilty of charges including conspiring to act as a foreign agent without notifying the U.S. Attorney General, a requirement under the Foreign Agents Registration Act enacted in 1938 to combat foreign propaganda.

This case highlights the ongoing challenges in counterintelligence efforts and the complex nature of dual citizenship, which is not officially recognized by China. It also underscores the importance of the U.S. citizenship oath, which includes a pledge to renounce allegiance to foreign states.

As encrypted messaging becomes increasingly common for both legitimate and illicit communications, cases like Wang's serve as a reminder of the evolving landscape of international espionage and the need for vigilance in protecting national security interests.