Jameson's "The Years of Theory": Unraveling French Thought's Political Legacy

Fredric Jameson's book explores French theory's evolution, highlighting its political roots and relevance. The work challenges misconceptions and examines theory's potential in the neoliberal era.

"French theory" often elicits strong reactions, but Fredric Jameson's "The Years of Theory" offers a fresh perspective on its political significance. The book, based on Jameson's 2021 online seminar at Duke University, examines French philosophy's evolution from the post-World War II era to the present day.

Jameson argues that French theory emerged as a response to specific historical and geopolitical contexts. He divides its development into four periods:

- Post-war liberation (1940s-1950s)

- Algerian War and structuralism (late 1950s-1960s)

- Post-May 1968 era

- Globalization period (1980s onwards)

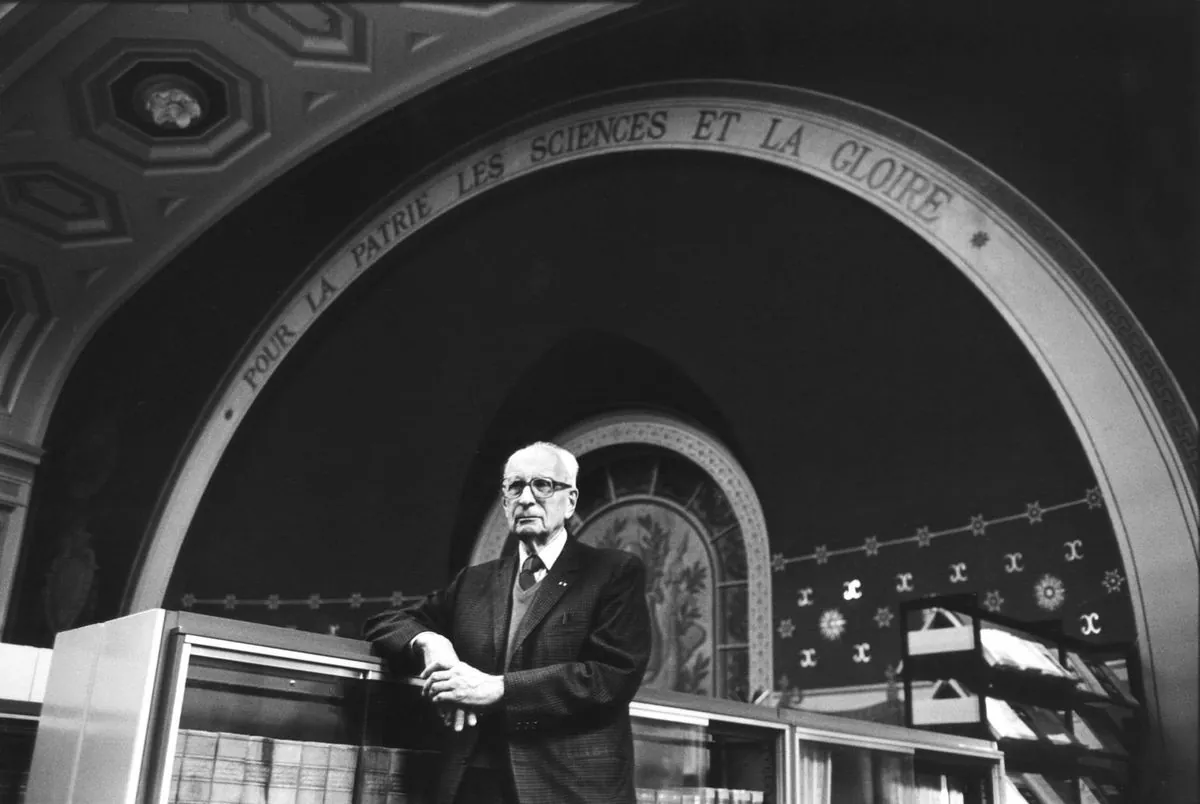

This framework highlights how French thinkers addressed philosophical problems arising from national events. For instance, Jean-Paul Sartre's existentialism in "Being and Nothingness" explored personal agency and identity in the post-war period. Later, structuralism, exemplified by Claude Lévi-Strauss's work, gained prominence during the Algerian War.

The May 1968 uprisings in France marked a shift towards examining trans-individual forces. Key figures of this period included Jacques Lacan in psychoanalysis, Gilles Deleuze with his concept of the "concept," Michel Foucault exploring power dynamics, and Jacques Derrida deconstructing philosophical traditions.

Jameson contends that French theory's reception in America often overlooked its political dimensions. While it influenced movements like third-wave feminism, critics like John Searle dismissed it as obscurantist. François Cusset argued that the transplantation of French ideas to American settings erased their political radicalness.

The book emphasizes theory's connection to the pursuit of an "autonomous France" between World War II and the rise of neoliberalism. However, with France's integration into the European Union and the end of the Soviet Union, theory lost its political bearings.

"The most successful part of neoliberalism was to have persuaded us that the future is here: We have the market, and we don't need anything else."

Despite this bleak assessment, Jameson suggests that theory's ability to imagine a collective future remains possible. He encourages identifying and solving shared problems, particularly in ethics, art, and neuroscience.

Contemporary scholars like Anna Kornbluh are applying theoretical traditions to examine aesthetic modes and mobilize groups for concrete political goals, such as unionizing Amazon workers. Extra-academic institutions like the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research continue to cultivate theory.

Jameson concludes that while the conditions that fostered French theory may have changed, its conceptual tools remain valuable for philosophizing collective social life in the face of globalization. As he notes, referencing Herbert Marcuse, theory still has an authoritarian figure to rebel against: globalization itself.