Bacteria Found to Break Down Plastic, Offering Hope for Pollution Solution

Scientists discover bacteria that can convert PET plastic into food, potentially addressing global pollution. The study reveals a six-step process, but optimization is needed for practical application.

In a groundbreaking discovery, scientists have identified a bacteria capable of breaking down plastic and using it as a food source. This finding, published in Environmental Science and Technology on October 3, 2024, could potentially offer a new approach to combating one of Earth's most pressing pollution problems.

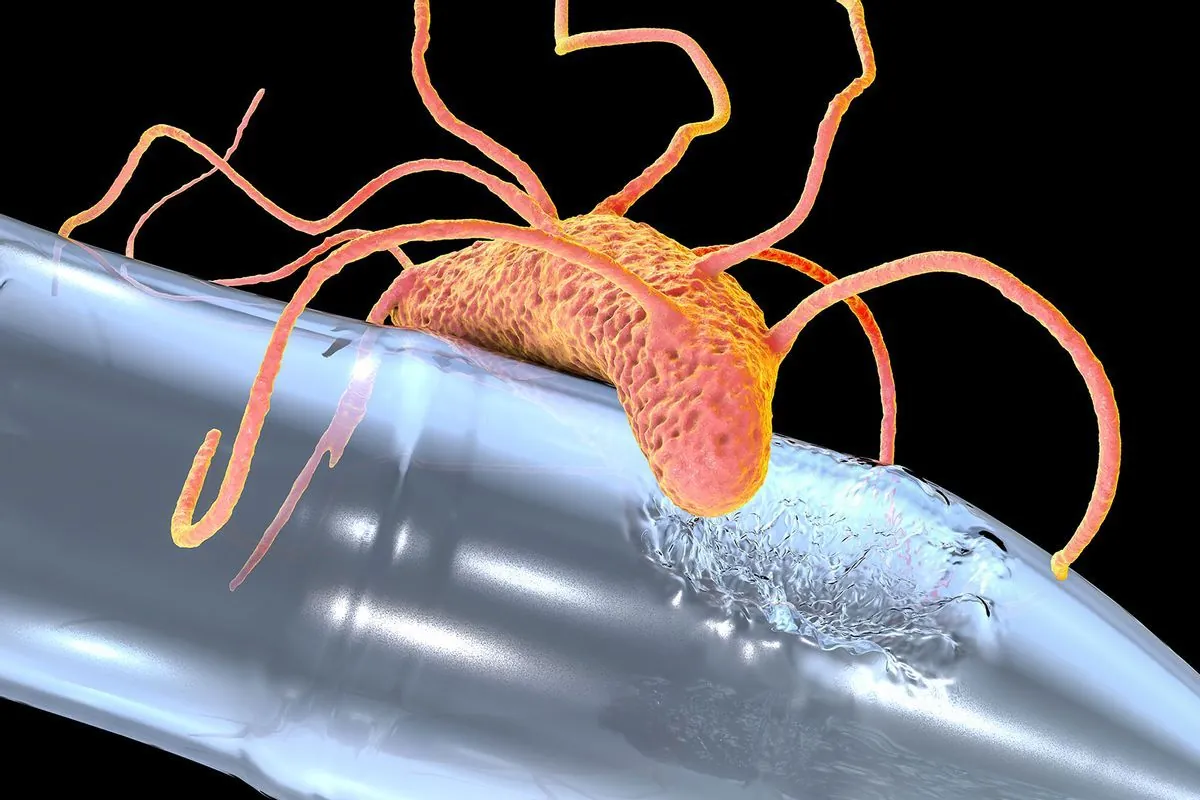

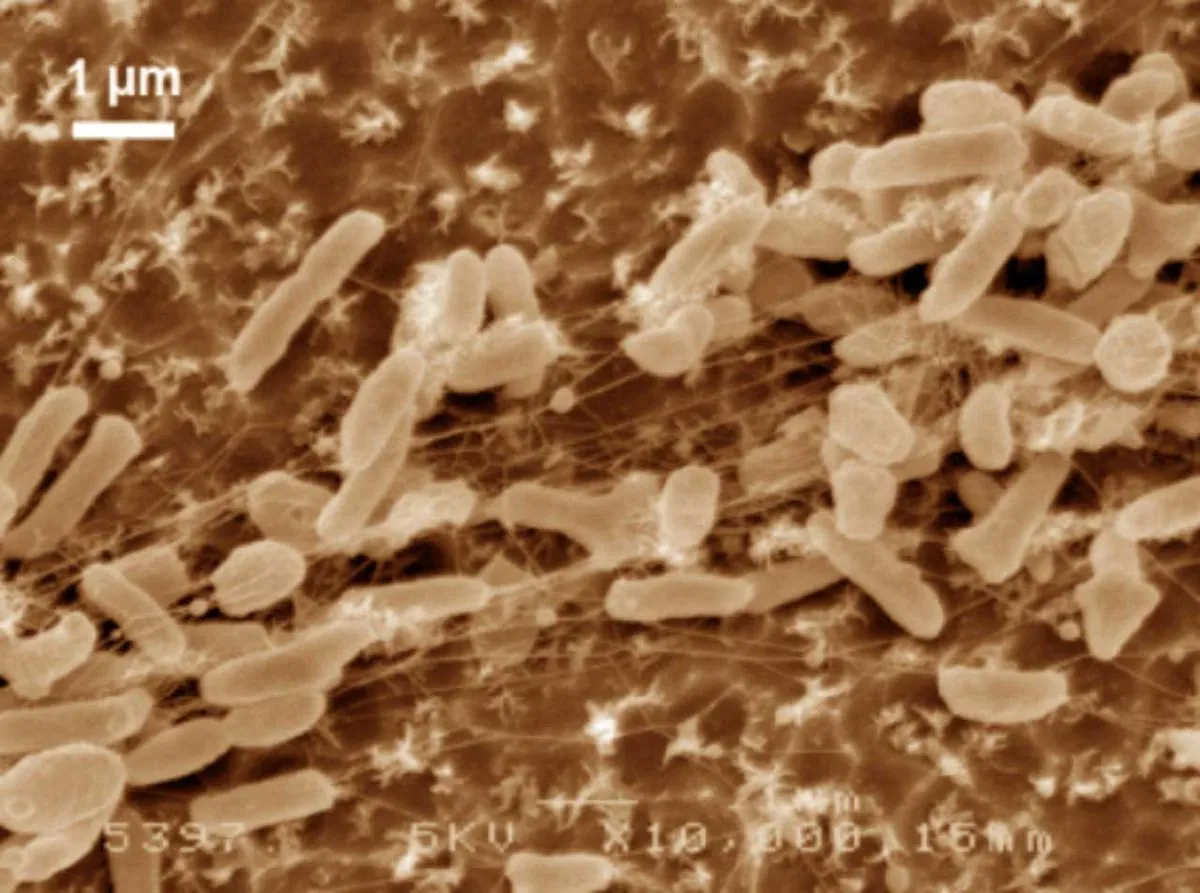

The study focuses on Comamonas testosteroni, a bacteria commonly found in wastewater. Unlike most bacteria that thrive on sugar, C. testosteroni has shown a preference for more complex materials, including polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a plastic widely used in single-use food packaging and water bottles.

PET, first synthesized in North America by Dupont chemists in 1941, currently accounts for approximately 12% of global solid waste, with an annual production of 90 million tons. The global PET market was valued at $24.49 billion in 2015, highlighting its significant economic and environmental impact.

The research team, led by Ludmilla Aristilde, associate professor at Northwestern University, has meticulously documented the bacteria's plastic-consuming process. Through a series of six complex steps involving imaging and gene editing techniques, the scientists revealed how C. testosteroni physically breaks down plastic before chemically processing it into a carbon-rich food source called terephthalate.

Nanqing Zhou, a lead author on the study, compared this process to human consumption of beef, emphasizing the multi-step nature of breaking down complex materials. The researchers' detailed examination allowed them to identify the specific enzyme responsible for converting inedible plastic into a digestible substance.

While this discovery presents a promising tool for combating pollution, it's important to note that the process is not yet ready for immediate large-scale application. Rebecca Wilkes, another lead author, explained that the bacteria currently take several months to break down plastic chunks, which is significantly slower than desired for practical pollution management.

"There's a lot of different kinds of plastic, and there are just as many potential solutions to reducing the environmental harm of plastic pollution. We're best positioned to pursue all options at the same time."

This research adds to the growing arsenal of solutions being explored to address plastic pollution. PET, despite being the most widely recycled plastic globally, can take up to 450 years to decompose in landfills. The development of bacterial decomposition methods could complement existing recycling efforts, which include the use of PET in producing polyester fibers for clothing and its application in various industries from automotive to medical implants.

As scientists continue to optimize this process, potentially by providing additional food sources like acetate to promote bacterial growth, the hope is that C. testosteroni could become an efficient tool in wastewater treatment plants and landfills. This discovery underscores the untapped potential of environmental microbes in providing sustainable solutions to our most pressing ecological challenges.