Morisot and Manet: Love, War, and the Birth of Impressionism

Sebastian Smee's "Paris in Ruins" explores how the Franco-Prussian War shaped Berthe Morisot and Édouard Manet's art and relationship, illuminating the birth of Impressionism amidst national turmoil.

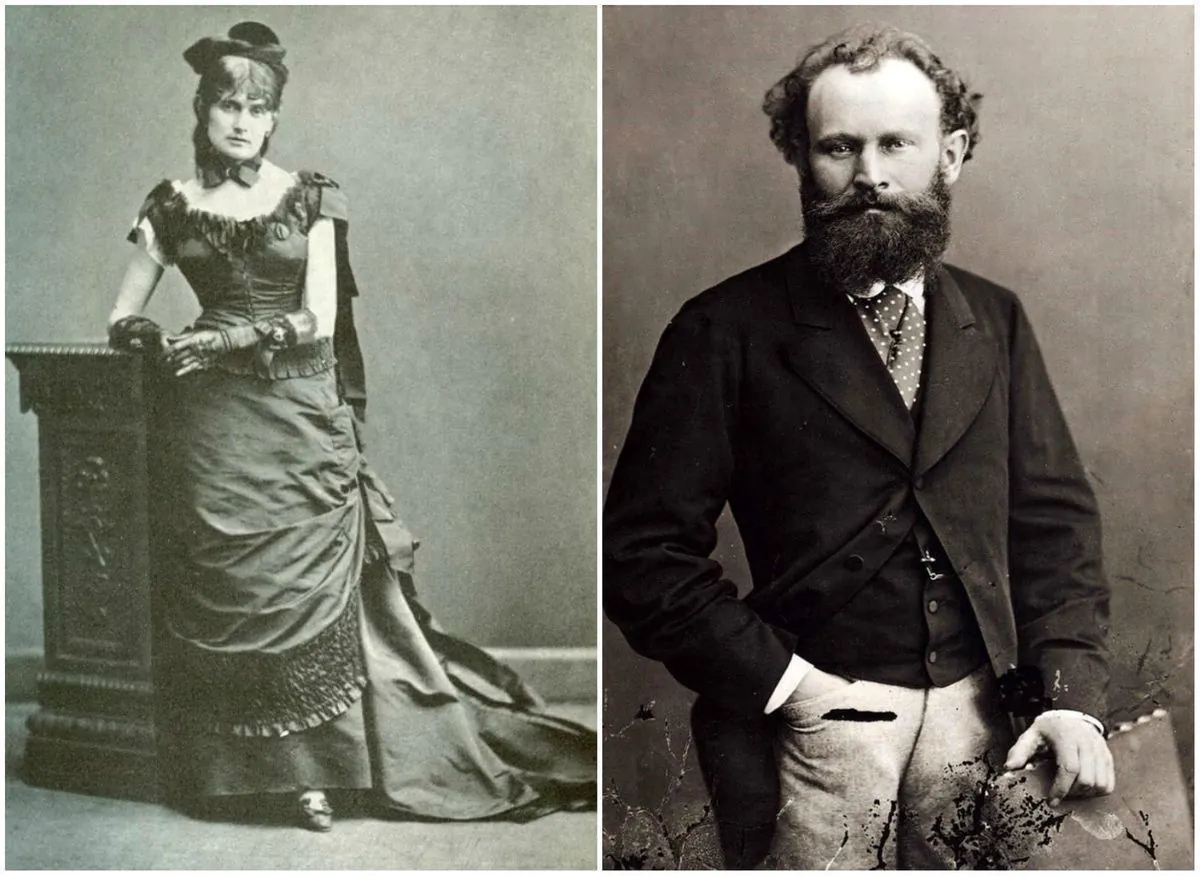

Berthe Morisot and Édouard Manet emerged as pivotal figures in the birth of Impressionism, a movement that revolutionized art in the late 19th century. Their story, intertwined with the tumultuous events of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, is vividly portrayed in Sebastian Smee's "Paris in Ruins: Love, War, and the Birth of Impressionism."

Morisot, renowned for her large, expressive eyes, captivated Manet, inspiring several of his portraits. However, her significance extended far beyond being a muse. As one of the founding members of the Impressionist movement, Morisot's artistic vision was shaped by her studies with landscape painter Camille Corot and her interactions with contemporaries such as Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

The Franco-Prussian War, which began in July 1870, and the subsequent Paris Commune of 1871, collectively known as "the Terrible Year," provided the backdrop for the development of Impressionism. While these events left Paris in ruins, Impressionist artists, including Morisot and Manet, chose to focus on fleeting moments of beauty rather than depicting the destruction directly.

"Berthe Morisot lived in her great eyes."

This approach was not a denial of the tragedy but a response to the newfound appreciation for life's transience. The Impressionists' emphasis on capturing ephemeral light and everyday scenes reflected a "new and suddenly deeper sense of existential fragility," as Smee notes.

Morisot and Manet's experiences during the siege of Paris profoundly influenced their artistic development. Unlike many of their colleagues who fled the city, they remained in Paris throughout the ordeal, enduring food shortages and isolation. This shared hardship deepened their bond and left an indelible mark on their post-war works.

Their relationship, however, was complicated by societal constraints. Despite their mutual affection, Manet was married, and both were bound by the conservative norms of Parisian bourgeois society. In December 1874, Morisot married Manet's younger brother, Eugène, a decision Smee describes as choosing "the next best thing" to the man she truly loved.

The paintings produced by Morisot and Manet in the aftermath of the war reveal striking similarities. Their works featured "strange, flat, barely legible pattern[s]" and contrasting motifs of light and dark, executed with distinctive brushstrokes that set them apart from other Impressionists like Claude Monet and Renoir.

Smee's analysis of their art as a "conversation on canvas" offers insight into how these two artists transformed their experiences of love, war, and societal restrictions into groundbreaking works. Their ability to express "things that can't be put into words" through paint exemplifies the power of art to convey complex emotions and experiences.

The story of Morisot and Manet is set against the broader context of the Impressionist movement, which originated in France in the 1860s and 1870s. The first Impressionist exhibition, held in Paris in 1874, marked a turning point in art history. Morisot was the sole female contributor to this landmark show, underscoring her significance in the movement.

Impressionism's emphasis on outdoor painting (en plein air) and capturing the effects of natural light was facilitated by the invention of paint tubes in the 1840s. The movement's influence extended beyond France, inspiring various artistic styles and leaving an indelible mark on the world of art.

As we reflect on Morisot and Manet's story, we are reminded of the enduring power of art to transcend personal and historical challenges. Their legacy, along with that of their fellow Impressionists, continues to captivate audiences worldwide, with the Musée d'Orsay in Paris housing the world's largest collection of Impressionist art.

Sebastian Smee's "Paris in Ruins" offers a compelling narrative that interweaves personal relationships, historical events, and artistic innovation. It provides a fresh perspective on the birth of Impressionism, illuminating how moments of crisis can spark profound creativity and cultural transformation.