Nissan Workers Learn Sign Language, Breaking Barriers for Deaf Colleagues

At a Nissan plant in England, workers are learning British Sign Language to better communicate with deaf teammates. This rare initiative is improving workplace inclusivity and team relationships.

In a remarkable display of workplace inclusivity, the entire 25-member bumper-paint team at Nissan's Sunderland plant in England has embarked on learning British Sign Language (BSL). This initiative, which began approximately eight months ago, aims to break down communication barriers with their deaf colleagues.

Michael Connolly, a 45-year-old deaf autoworker at the plant, expressed his enthusiasm for his teammates' efforts with a universal gesture: two thumbs up. The ability to engage in everyday conversations about family, vacations, and television programs has significantly improved Connolly's work experience.

"I'm glad they have all learned sign language for us because I can talk and I lipread the hearing person, but I have my limits. If you reverse the situation and the hearing person can sign and speak, they have no limits."

This initiative is part of a broader effort to enhance efficiency at the Sunderland facility, which produces Qashqai and Juke sport utility vehicles. The bumper-paint team's decision to learn BSL goes beyond the plant's general measures to improve training and increase visual aids during briefings.

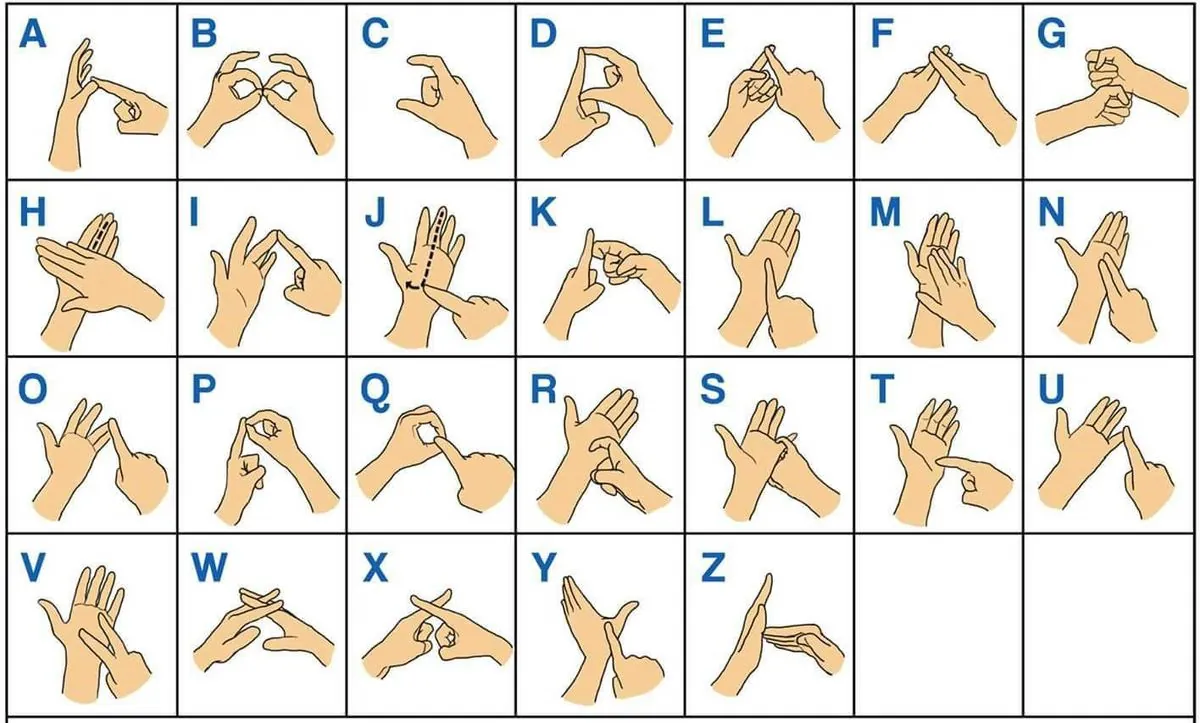

BSL, recognized as an official language in the UK since 2003, has a rich history dating back to 1570. With approximately 151,000 users in the UK, it possesses its own distinct grammar and syntax, separate from spoken English. The language's regional variations add to its complexity, with different signs used across various parts of the country.

Supervisor John Johnson acknowledged the initial challenge of mastering BSL's combination of gestures, facial expressions, and body language. However, the experience has provided valuable insight into the daily challenges faced by deaf workers in a predominantly hearing environment.

The rarity of such initiatives in workplaces is highlighted by Teri Devine, associate director for inclusion and employment at The Royal National Institute for Deaf People. She emphasizes that while many employers attempt to engage with deaf workers, few go as far as learning sign language. Research indicates that deaf individuals, particularly BSL users, often feel isolated at work.

The importance of this initiative becomes clear when considering that even the most skilled lip readers typically comprehend only 30% to 40% of a conversation. By learning BSL, the Nissan team has significantly improved communication and inclusivity.

Cary Cooper, a professor of organizational psychology and health at the University of Manchester, points out the numerous benefits of workplace kindness and inclusivity. The improved communication within the bumper-paint team has led to stronger relationships and more meaningful interactions beyond work-related topics.

This initiative reflects a growing awareness of BSL's importance in British society. Since the first BSL/English dictionary was published in 1992, there has been increased visibility of BSL interpreters on UK television during important broadcasts. The COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted the need for BSL interpretation during government briefings.

As the Nissan team continues to break down barriers through language learning, their efforts serve as an inspiring example of how workplaces can foster inclusivity and improve team dynamics. This initiative not only enhances communication but also celebrates the rich cultural and linguistic diversity that BSL represents.