1n 1986, Jewish Hollywood legend Paul Newman decided it was time to set the record straight about who he really was. His goal was to counter the tabloids’ lies and exaggerations, but also confront the inner demons that had dogged him since childhood. Publishing a memoir would be a good way to do this, and Newman — by then in his 60s — was finally ready.

The actor, philanthropist, race car driver and political activist worked on a book for five years with his good friend, writer Stewart Stern. But after sitting down for countless hours of taped interviews with Stern — and asking many friends, colleagues and family members to do the same — Newman mysteriously dropped the project, never to pick it up again. (“Rebel Without a Cause” writer Stern died in 2015.)

No one knows what happened to the tapes — they may have been burned. But recently, thousands of pages of transcripts of the interviews done between 1986 and 1991 showed up in the basement of the Connecticut home that Newman shared with his wife of 50 years, actor Joanne Woodward, and in a family storage unit.

Newman’s daughters decided that what their father thought about himself and his life, as well as what others thought about him, deserved to be shared with the world. The result is the illuminating memoir, “The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man,” edited by David Rosenthal and published this past October, 14 years after Newman’s death from cancer at age 83.

In a recent interview with The Times of Israel from his home in Brooklyn, Rosenthal, 69, said that Newman’s daughters (including Melissa Newman, who wrote the book’s foreword, and Clea Newman Soderlund, who wrote its afterword) were keenly aware of the tension between their desire to present their world-famous father in a positive light and the transcripts’ revelations of Newman’s many faults and surprisingly constant self-doubt and guilt.

Get The Times of Israel's Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories

“He was a very self-deprecating man, and they would be the first to say that he was also a rather difficult man because he was very reserved about some things. He was very loving and adoring of them, but a very absent father. The fact that he had a whole other family before he met Joanne was a very complicated thing for him and the daughters,” Rosenthal said, referring to Newman’s 1949-1958 first marriage to Jackie Witte.

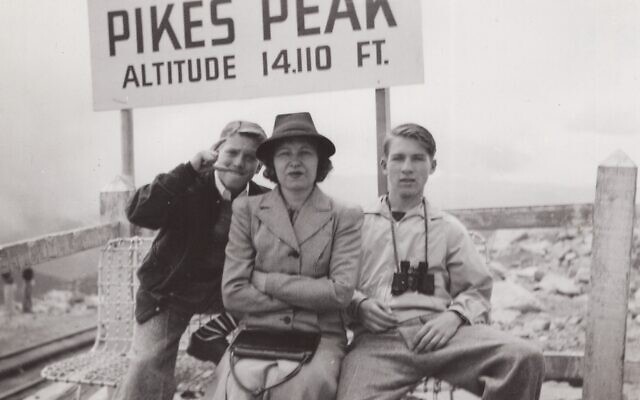

Paul Newman (right) and his brother Arthur Newman, Jr. with their mother Tress Newman on a visit to Pikes Peak, Colorado, in the late 1930s. (Newman Family Collection)

“I think they took him at his word in what he says in this material, which is that he wanted to tell his family some things about him that he hadn’t said. It was a cathartic thing to some extent. He dealt with the breakup of his first marriage [following a four-year affair with Woodward] and the death of his son [Scott from a drug and alcohol overdose in 1978]. He talked about these things that in profile articles over the years he was not forthcoming about,” Rosenthal said.

Champion beer chug-a-lugger

The son of a sporting goods store owner in Shaker Heights, Ohio, Newman pursued acting as a way of avoiding going into the family business. Other than setting his college’s beer chug-a-lugging record, Newman was not a stand-out in any particular way. Spared from direct combat experience, Newman drank, pranked, and gambled his way through much of his WWII military service in the Pacific.

After graduating from Kenyon College and beginning a degree in directing at the School of Drama at Yale University, Newman was accepted to the famed Actors Studio in New York, which produced some of the mid-20th century’s greatest actors, including Marlon Brando, James Dean, Julie Harris, Eli Wallach, and Anne Jackson.

‘The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man: A Memoir’ by Paul Newman, edited by David Rosenthal. (Knopf)

“How, I wonder, did I ever pass that audition? They didn’t, and couldn’t have, responded to my acting. I’m sure the other actors there wondered, ‘How did this son of a bitch get in here?'” the insecure Newman wrote.

Statements like this permeate the sections of the memoir dealing with Newman’s early- and mid-career years. He attributed his success in large part to his stand-out good looks.

“He was so extraordinarily beautiful. He had to have known he won the gene lottery somewhere,” Rosenthal said.

Newman also believed he benefited from luck and his tenaciousness, to keep working at something until it was right. Newman, the star of classic films such as “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” “The Hustler,” “Hud,” “Cool Hand Luke,” “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” and “The Sting” just couldn’t see what others did — that he had an innate talent for acting. He worked hard at his craft, developing ways to compensate for what he was convinced he lacked naturally.

Something rotten in the state of Ohio

Despite all the interesting reflections on Newman’s years in the theater and film by him, co-stars and great directors such as John Huston and Elia Kazan, the heart of “The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man” lies with revelations about Newman’s upbringing and family life as a child and teenager.

As early as page six, it is evident that something was not right.

Arthur Newman and Paul Newman (right) in the mid-1930s (Newman Family Collection)

“It was…in the dining room that [older brother] Art and I would bang our heads against the wall. Literally. We did it in secret until the dent got big enough for my parents to notice. This was not some tippy-toe banging; this was a serious whacking that took down the plaster behind the wall covering. We must have knocked our fucking brains out. It was our own Wailing Wall. I couldn’t take my rage out on anybody my size, so I took it out against the wall,” Newman wrote.

Newman and his brother were the products of a complicated marriage between the Jewish Arthur Newman and the Catholic-turned-Christian Scientist Slovakian immigrant Teresa (Tress) Fetzko. Having escaped an abusive first marriage, Teresa met Arthur and got pregnant. The couple was unmarried when Paul’s older brother Arthur Jr. was born, and Arthur only agreed to wed Teresa under pressure from his family to do the respectable thing.

Although a successful businessman and good provider, Newman’s father was a demanding, emotionally distant excessive drinker. His mother could not see beyond herself to the emotional needs of her children. Newman viewed his mother’s little dogs as metaphors for himself.

“I was like one of those poor fucking dogs of hers who became cancerous and so obese they could hardly move, and my mother would keep feeding them chocolates until she killed them with kindness. My mother was oblivious to the damage being done. Her need to bestow affection not only overwhelmed the object she bestowed affection upon, but had nothing to do with that object,” he wrote.

The Joanne Newman-Paul Woodward wedding party in 1958. (Newman Family Collection)

According to Rosenthal, the lack of self-worth expressed by Newman in the transcripts is not surprising.

“[His parents’ behavior] made him feel not worthy — not worthy of the father, and his mother always said she loved him regardless of what he did, so anything he did couldn’t be worth anything,” Rosenthal said.

Newman’s father died in his 50s. His mother lived much longer, but at one point Newman cut off ties with her for some 15 years to protect himself from their toxic relationship. Despite a reunion, they only saw one another several times after that. Even when Teresa became terminally ill, “we never discussed our rift, and she never apologized,” Newman wrote.

A Jew, loud and proud

In the book, there is no mention of religious education or the marking of Jewish holidays or milestones with Newman’s paternal extended family. Rosenthal said he searched for a record of Newman having had a bar mitzvah ceremony but could find none.

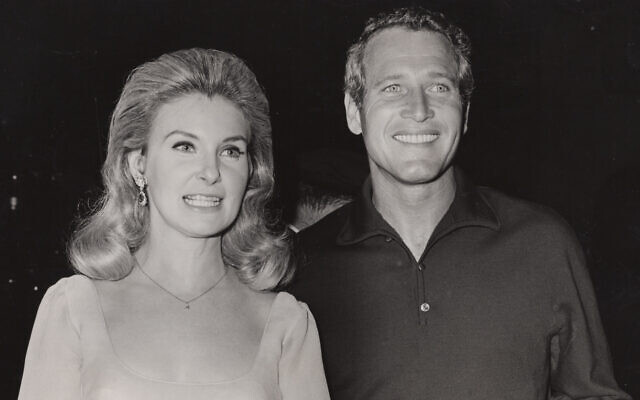

Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman in the late 1960s. (Kas Heppner/Newman Family Collection)

Although clearly secular, Newman’s father read the daily Cleveland Jewish newspaper. His parents were lifelong members of the local Jewish country club, and they kept their synagogue seats for life so they could be buried in the Jewish cemetery. Newman, however, speaks of his own Jewish identity only in terms of having had to deal with antisemitism.

“He absolutely self-identified as Jewish. I think he got taken with the idea of being the outsider, the rebel. So if the other kids were keeping him out of the high school fraternity, or he got into a fight in the service after being called a slur, he wanted to be Jewish because it was more heroic and he always wanted to be a bit of a hero,” Rosenthal said.

When Newman’s career began to really take off, it was suggested to him by Jewish producer Sam Spiegel and others that he change his name to something more WASPy, as many Jewish actors had.

“I could have eliminated my Jewish roots, simply obliterated the thing that had caused me so much discomfort. But it seemed more of a challenge to me to keep my real name, to insist upon it as a badge,” Newman wrote.

Editor David Rosenthal at home in Brooklyn, NY (David Burnett/Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

While continuing to act and direct, Newman got into race car driving in the 1970s. In 1982, Newman launched Newman’s Own Salad Dressing, which grew into a popular food line (including organic products). All profits ($600 million to date) go to the Newman’s Own Foundation, which supports children’s health, nutrition, and well-being internationally.

Newman founded the SeriousFun Children’s Network to provide children living with chronic or life-threatening illnesses a free-of-charge fun and safe overnight camp experience. The Jordan River Valley Camp in northern Israel is part of the network.

Newman wrote about going through life with his “own type of evolving emotional anesthesia.”

It would seem that in the 17 years between dropping the memoir project and his death, the anesthesia was wearing off.

“By accounts of the family, he had not cleaned up all of his foibles, but he really spent those years it seems trying to compensate for the crap he had pulled. The camps, the charitable good works, spending time with the family — all those things. He never stopped drinking, but he was no longer a serious drinker by the mid-90s,” Rosenthal said.

“Maybe that is the reason he stopped working on the book. Maybe the person he was soon becoming — or at least wanted to become — was a different person than the one he had been describing,” he said.