The cabinet on Sunday voted to extend for an additional five years a veil of secrecy over the activities of a controversial state-owned oil infrastructure conglomerate, despite receiving more than 300 objections to the move.

The extension is subject to approval by the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee.

The Europe Asia Pipeline Company — formerly the Eilat Ashkelon Pipeline Company — is the best-known of three state companies established by Israel decades ago in a secret partnership with the shah’s Iran.

Until the 1979 Islamic revolution and the severing of bilateral relations, Iranian oil was quietly picked up by Israel in Eilat on the Red Sea and transported overland to Ashkelon on the Mediterranean, from where it could be shipped to Europe.

It was also used by Israel for internal purposes.

Get The Times of Israel's Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories

If Sunday’s decision is approved, the law will continue to ban the publication of information about the EAPC or any of the three companies associated with the original Israel-Iran deal — the EAPC’s predecessor, the Eilat Ashkelon Pipeline Company, the Eilat Corporation SA, and Trans Asiatic Oil, Ltd. Each fulfilled a different part of the agreement.

The prohibited information includes the identity of shareholders, details about oil deals, company worth, and management issues.

The few subjects that can be made public include the environment, planning and building, business registration, safety measures, permits, licenses and orders given by state bodies, supervision and enforcement carried out by bodies such as the Environmental Protection Ministry and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, and violations and malfunctions.

According to a Justice Ministry appendix to the decision approved Sunday, opponents responding to a draft order put out for public comment noted the EAPC’s poor pollution record and charged that the confidentiality was too wide and all-encompassing, and did not allow any oversight of the companies’ activities.

They quoted officials from the EAPC and the Government Companies Authority who favored lifting the secrecy requirement.

Itzik Levy, CEO of the Europe Asia Pipeline Company, attends a meeting of the Knesset Internal Affairs and Environment Committee on November 29, 2021. (Noam Moshkovitz, Knesset Spokesperson’s Office)

But the Justice Ministry responded that the original order, and its extension, was aimed at “securing the interests of the state and not the company,” and that it did not exempt the companies involved from complying with other laws, such as environmental ones.

With the validity of the order due to run out on February 15, the government recommended extending it “in light of the lack of any change in the circumstances.”

The Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel, one of many organizations opposing the secrecy extension, said the government would have to bear responsibility for the lack of public transparency and official supervision over the EAPC’s activities, and any environmental disaster that might unfold as a result of the company’s activities in the ecologically sensitive Gulf of Eilat.

The EAPC has raised the ire of a long list of organizations and individuals over what they see as a poor environmental record.

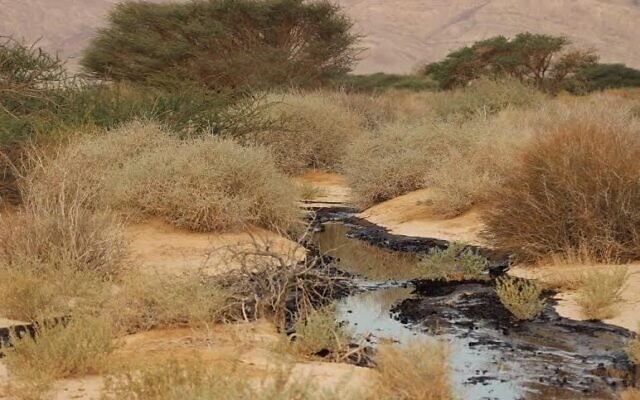

An oil spill in Evrona, southern Israel, caused by the rupture of a Europe Asia Pipeline Company pipe, December 5, 2014. (Noam Weiss, Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

In 2014, for example, the company was responsible for Israel’s worst environmental disaster when a pipe burst, sending some 1.3 million gallons of crude oil into the Evrona Nature Reserve in southern Israel.

Hostility towards it among environmentalists increased after it signed a 2020 deal with a consortium of Israeli and United Arab Emirates businessmen to use its terrestrial pipeline infrastructure to channel Gulf crude from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean.

Former environmental protection ministers, the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, the local coastal authorities, a forum of some 20 environmental organizations, and scores of scientists and Eilat residents oppose the UAE agreement.

They warn that just one leak could spell catastrophe for the globally important coral reefs off the coast of Eilat in southern Israel, and the economy of the city and the Gulf of Eilat, as well as Jordan’s Aqaba.

Marine life at a coral reef in the Red Sea waters off the coast of Israel’s southern port city of Eilat, on February 10, 2021. (MENAHEM KAHANA / AFP)

It is still unclear which, if any, government ministries, knew about the deal with the Israeli-UAE consortium before it was signed. The contents have never been made public.

The EAPC is still fighting the Environmental Protection Ministry in the courts over the latter’s refusal to allow it to fully implement the UAE deal.

The previous minister, Tamar Zandberg (Meretz), ruled that the company had failed to carry out a sufficient environmental risk survey — a claim the EAPC denies.

It remains to be seen how Zandberg’s replacement, Likud’s Idit Silman, will deal with the issue. Her new director-general, Guy Samet, who helmed the ministry until 2020, returns after serving as the Energy Ministry’s Director of Natural Resources Administration and Petroleum Commissioner.

Because of the secrecy, there is no way to explain exactly why the confidentiality order — in place since the 1960s — still needs to be extended.