DETROIT — As a teenager in 1960, Sy Ginsberg grabbed a broom and took a part-time job at Lou’s Deli in downtown Detroit. Even by then, the eatery had blossomed into an icon a neighborhood full of competitors during the golden age of Jewish life in the inner city.

Though the idea of that teen turning into a delicatessen magnate might seem far-fetched, Ginsberg has become exactly that. The Detroit-based company he founded in 1981, United Meat & Deli, supplies over 150,000 pounds per week of corned beef, pastrami, and other deli meats to restaurants and wholesalers throughout the Midwest, and as far away as Alaska and Texas. It’s a far cry from the closet-sized 35-seat deli he bought along with a fellow Lou’s coworker in 1968 when he was just 23 years old.

In a way, delis are Ginsberg’s birthright: His mother — originally a rural Kentucky girl — met his father, a Jewish Belarussian immigrant, while waitressing at a deli.

In 1975, after expanding his heimish deli into a much bigger space in a heavily Jewish area of the up-and-coming suburb of Southfield, Ginsberg found instant success.

“We were very, very blessed,” he says. “The minute we turned the key and opened the door, people were standing in line. My mother was the head cook in the kitchen — she made the mushroom barley soup, and the matzah balls, and the kishka. Everything was homemade, everything.”

Get The Times of Israel's Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories

But, says Ginsberg, after five years at the new location, he was “totally burned out. I couldn’t take it anymore. It was 80 hours a week, two divorces later. A gentleman came in and said, ‘Hey, you want to sell your place?’ I said, have a seat, let’s start talking.”

After selling the restaurant, Ginsberg got involved in the wholesale and distribution of corned beef, which he brought in from Chicago.

“And then one day, I said, hey, I’ve been to enough corned beef plants around while I was just acquiring all this knowledge. I’ve seen it done, I can do this myself. I fulfilled all the USDA requirements, and we started making corned beef,” Ginsberg says.

In the intervening years, Ginsberg’s name has become synonymous with deli. The best Detroit delis proudly boast that they carry his eponymous corned beef, and the famous Zingerman’s in nearby Ann Arbor hasn’t purchased meat from anyone else since it opened in the early 1980s. Author David Sax even partly dedicates his well-known book, “Save the Deli,” to Ginsberg for being such an exhaustive source.

For his part, Ginsberg is more than happy to share his knowledge and prides himself on being a deli consultant — a service he provides for free to new customers, coming in and working in the kitchen himself for a couple of days to show them how it’s done.

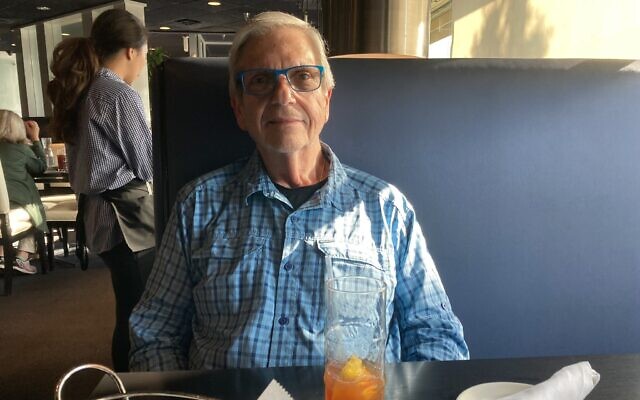

The Times of Israel recently sat down with Ginsberg at the Stage Deli, another Detroit institution that dates back to 1962 whose original founder Jack Goldberg pioneered the double-baked rye. It also happens to be a Ginsberg customer. The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Deli authority Sy Ginsberg at the Stage Deli in West Bloomfield, Michigan, September 13, 2022. (Yaakov Schwartz/ Times of Israel)

The Times of Israel: Is it weird that I asked you to meet me here in the Stage Deli, of all places? You probably spend a lot of time in delis already.

Sy Ginsberg: No, not at all. I mean, to me, this is my favorite Detroit deli — the best Detroit deli, as far as I’m concerned. They do a great job.

A lot of delis carry your meat. So what’s the difference between what’s happening at the Stage versus what’s happening at other delis like the Bread Basket Deli, or Zingerman’s in Ann Arbor?

Well, basically, there’s a little bit of a difference in the preparation, but that’s minimal. I think a lot of it has to do with the ambiance. Zingerman’s is so well known because of their merchandising. They started out as one little deli on the corner of Detroit Street and Kingsley or Catherine in Ann Arbor, with no real experience whatsoever, and they built a community of, I think, 11 businesses now. When they first opened up, there were a couple of delis that had tried and failed there, and Zingerman’s was determined to not let that happen — but they didn’t know anything about the deli business. There’s actually a plaque up there in one of the eating areas recognizing me for making the first sandwich that ever went out at Zingerman’s.

You actually made it yourself?

So what I used to do — because when Zingerman’s opened, I was just starting. I had sold my deli in Southfield, and I was working in wholesale and distribution, and I opened up my own company and started manufacturing corned beef. I was a one-man operation. I delivered corned beef out of the back of my Volkswagen, and I would stay and work lunch hour with them on the sandwich board, training their staff. And consequently, I was showing them how to make the sandwiches. So I made the first sandwich that ever went out at Zingerman’s.

Is there a difference in the way the meat is prepared for each place?

Well, I mean, some people will buy the raw corned beef, and they will cook it longer than others. If you cook it a little longer, it gets a little more soft and tender, but you lose a little bit in the yield aspect of it. So some people like to cook it less, but then they have to slice it very thin so that it’s not tough. That’s one aspect. I have some customers – which I don’t particularly care for it – but they will put pickling spice in the water when they cook it, because to me, that gives it more of the goyishe Irish flavor, which is okay for St. Patrick’s Day, but it’s not your Jewish style corned beef.

But the product that you deliver is mostly the same thing that comes to the door of Stage and Bread Basket?

Basically, yes. There might be some differences in the trim. Some might like a little less fat on it. Some might like a little more fat on it. The price has something to do with it, like the Bread Basket. He might want a little fattier piece of meat because he’s servicing the inner city where they like a little schmaltzy corned beef. Out here in the suburbs, people want something maybe a touch less fatty.

I like it leaner. Does that make me a bad Jew?

No, not at all. It’s a personal preference.

Everybody says that you’ve got to like it fatty.

The flavor of the meat is in the fat and the juiciness of it. So, yeah. But that’s one aspect of it. But besides selling the meat raw, where you cook it on-premises, we also sell it precooked, where we cook it in our facility. And that is something that a lot of places do if they don’t have the kitchen facilities or the help experience to cook it. But my personal preference is if I was opening a deli, I would want to cook it myself.

The Stage Deli in its original Detroit location, circa 1962. (Courtesy Stage Deli)

I read an article about double-baked rye where you were speaking with David Sax, author of “Save the Deli.” It turns out that it was actually started here in Detroit. Can you tell us about that?

It’s integral. The owner of this place [Stage Deli] is Steve Goldberg. Jack Goldberg was his dad. Jack Goldberg started the double-baked rye bread. What it is, is the delis get rye bread from a commercial bakery, and it’s got a little bit of a crustiness to it, but we put it in the oven and bake it for another 20 minutes or so, and it comes out just like that – nice and crispy crust, nice and warm. They hand slice it, and that’s where the double-baked rye bread comes from.

So there’s that, and then I just found out Topor’s pickles is also from here, which I never knew. Can you tell me a little bit more about Detroit’s contribution to deli history?

Well, basically, the double-baked rye bread is the one big one.

But at most of the delis in New York, pastrami is king. They sell probably 10 pastrami sandwiches to one corned beef sandwich there. It’s the other way around here. In New York, it’s pastrami or corned beef with mustard on it. That’s basically it. Here, the most popular sandwich is probably corned beef with coleslaw, onions and Russian dressing. And we started that. You don’t see that – I mean, you see it in other places now, but I think that the combination on that sandwich started here in Detroit. New York, they wouldn’t have anything to do with that.

Were there any famous delis around here?

Lou’s was the big name years ago. Yeah, just like David Sax has written in his book about all the delis that were in New York and disappearing, we had a lot of delis here. We had a good 25, 30 of them, and we’re down to just a couple now. Some places call themselves delis, but they’re really just sandwich shops. A deli has a big counter where you can see knishes and potato salad and coleslaw and halva and all the good things that you see in the deli there. You don’t see that except for maybe three places here in Detroit.

What do you gotta have on the menu if you want to call yourself a deli then?

Anyone can call themselves a deli.

Okay, if you want to be a deli.

I want to have mushroom barley soup, I want to have matzah ball soup, kreplach, stuffed cabbage, baked short ribs, gefilte fish, pickled fish, you know, look at the menu – all the stuff they’ve got here.

Deli case at the Stage Deli in West Bloomfield, Michigan, September 13, 2022. (Yaakov Schwartz/ Times of Israel)

I’m a sucker for kasha varnishkes, myself.

There you go, that’s another one. The best place for that kind of stuff is in Houston, Texas.

What?

Place called Kenny and Ziggy’s. Ziggy Gruber is the most unbelievable — you can see videos of him. There was a movie called “The Deli Man,” and it was a first-run movie, it was in the theaters, and it was kind of a biopic about him. He’s an unbelievable guy. He’s a New Yorker, and he has this big thick New York accent, and every third word might be a Yiddish word. He’s just the greatest. He’s a great customer and a very good friend. If you ever want to see a real deli, the most authentic New York deli, you’ve got to go to Houston. Number one in the country.

How do you feel about walking into a place and finding out that they have ham and cheese on the menu, or a breakfast sandwich with bacon on it, or macaroni and cheese, or other… what you might call goyish foods.

I don’t have a problem with it. I don’t have a problem with it because I eat it. I’m not observant. So I think that you need to have it with the way our people are assimilated now, and the culture. It’s there for people that want it. You don’t have to eat it if you don’t want to, nobody says you have to.

Believe me, I don’t want to.

I have a cousin who lives near me. It’s not a very Jewish area. And we go out to dinner frequently with her, and she will not eat pork, but she’ll eat shellfish. She’ll eat shrimp, she’ll eat lobster. I said, you don’t make sense. Which is it – either you are, or you aren’t. You’re a hypocrite. I egg her on, I needle her so much. And she says, it’s just me, it’s just what I’m comfortable with. So I say, okay, so I’m going to order pizza, and I’m going to have pepperoni on my side and no pepperoni on your side. And she goes, it’s a deal.

It’s funny because I grew up Orthodox, and among my family and friends it’s also a spectrum — everyone does their own thing.

I went to yeshiva on Dexter, in the old neighborhood in downtown Detroit, as a kid.

Really?

When I was 13 and I had my bar mitzvah, I told my parents that I’m done, I want nothing to do with Orthodox Judaism. They weren’t observant, but they sent me to the Hebrew school that was.

If you ever want to see a real deli, the most authentic New York deli, you’ve got to go to Houston. Number one in the country

Which school was that?

Yeshiva Beth Yehuda.

That’s where I went! But I went when it was already on Lincoln.

Ah, okay. But I wanted to have nothing to do with it because I did not like the way the rabbis bullied people, I did not like talking to people and hearing them say, don’t worry about it, God will take care of us. There’s only one person that’s going to take care of me, and that’s me. And that’s all there is to it.

Well, I can assure you nothing has changed. Where were your parents from — were they born here in the United States?

My father was born in Russia. Belarus, actually. And my mother was a hillbilly from Kentucky. She worked at a deli, and apparently she met my father at the deli there and they eloped and got married. My grandfather was very Orthodox, and he said that she had to convert, and she converted, and she made sure I went to Hebrew school and did all that.

Interior of the Stage Deli in West Bloomfield, Michigan, September 13, 2022. (Yaakov Schwartz/ Times of Israel)

What do you think about the future of deli in America?

Everything is kind of assimilating into one thing now. I’m not too worried about it from a business point of view because just about every bistro or restaurant nowadays has a Reuben sandwich on the menu. So it’s not going to hurt me too much business-wise. As far as the character of the deli, I think every big city will have a few. Houston, Las Vegas, LA has quite a number, still has a good half a dozen delis. In New York there’ll still be some. But it’ll be a destination place. It won’t be the kind of thing that we used to think about, where you go and you schmooze with your friends and you see people, which is what it was, how I remember the delis being when I was a kid. You’d go to Lou’s, or down the street was another deli called Whitey’s, or up the street was another deli called something else. And you’d go and you run into your friends and you’d schmooze.

When I was off work on Saturday nights the guys would all go out on dates, and afterward we’d drop our dates off and we’d all go back to Lou’s and hang out and talk about our accomplishments that evening – or our disappointments. And sometimes we’d sit around at Lou’s and wait till they closed – they closed at two in the morning – and as long as there were a couple of us who were employees there, they’d let us sit there and we’d play cards until five o’clock in the morning when the morning waitress would come in at six and throw us out.

Sunday was a busy time because the carry-out line would be lined up, people coming and buying. A pound of corn beef, and half a pound of pastrami, and a quart of potato salad, and a quart of coleslaw, and can you slice the rye bread for me, and a quart of Faygo Red Pop. Oh, and can I get a half pound of chopped liver?

We’d put it all in a bag, and we’d have a pencil in our ear, we’d put the numbers on the bag– we’d have to add it up on the outside of the bag and total it, and they’d go to the cashier and show them the bag. And that’s how we did it. That’s how I remember deli. In fact, I’m getting goosebumps just talking about it, but that’s how it was. Now it’s POS point-of-sale stuff with the computers and the waitresses, everything’s on a guest check or stuff like that. But that’s how I remember deli, and we’ll never see it again.