Two new related initiatives are making it easier for descendants of Jews who were persecuted, forced to convert to Christianity or expelled from the Iberian Peninsula in the 14th and 15th centuries’ Inquisition to reconnect with their roots.

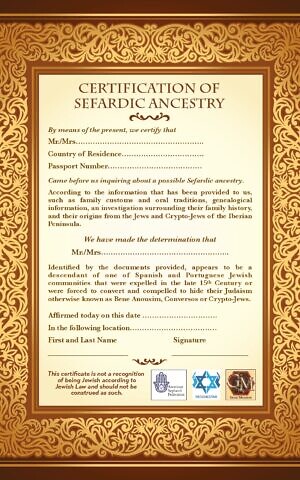

The first is a Certificate of Sephardic Ancestry, for which descendants of the Sephardic communities of Spain and Portugal who are not part of the organized Jewish community and not recognized by halacha (Jewish law), can apply. The certificate recognizes a person’s genetic or historical connection to Sephardic Jewry but is not official for religious purposes (such as conversion) or application for Spanish or Portuguese citizenship.

The certification is a joint effort of the American Sephardi Federation’s Institute of Jewish Experience; Reconectar, an organization dedicated to helping the descendants of Spanish and Portuguese Jewish communities reconnect with the Jewish people; and Genie Milgrom, an author, researcher, and genealogist who fully documented her unbroken maternal lineage 22 generations as far back as 1405 in pre-Inquisition Spain and Portugal.

“Many people have said that they wanted some level of recognition of their Sephardic Jewish ancestry. Having a certificate like this would be a point of pride for them,” said Ashley Perry, founder of Reconectar, which has a total of 20,000 followers on its English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Catalan Facebook pages.

“Recent academic and genetic research has demonstrated that there are as many as 200 million people, largely in Latin and North America and Europe, who have ‘significant Jewish ancestry,’ meaning at least five percent Sephardic DNA,” Perry said.

Get The Times of Israel's Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories

The Israel-based Perry, whose family’s original name was Perez, lobbies the Israeli Knesset and Jewish organizations to come up with appropriate responses to this increasing number of people uncovering their Sephardic Jewish past.

Genealogist Milgrom specializes in tracing the lineages of Crypto-Jews, also known as Anousim, Marranos, and Conversos. Crypto-Jews were Jews who outwardly presented as Christians but continued to practice Judaism in secret to avoid persecution in Medieval Spain and Portugal and their colonies. Many were denounced to the Inquisition as “Judaizers,” and often imprisoned, tortured, and killed (including by auto-da-fé, or burning at the stake). Those who survived may have retained some Jewish customs, but their core Jewish identity disappeared over generations, especially as they dispersed and settled in the New World.

This was the case with Milgrom’s own family, who were fervent Catholics and ended up in Cuba.

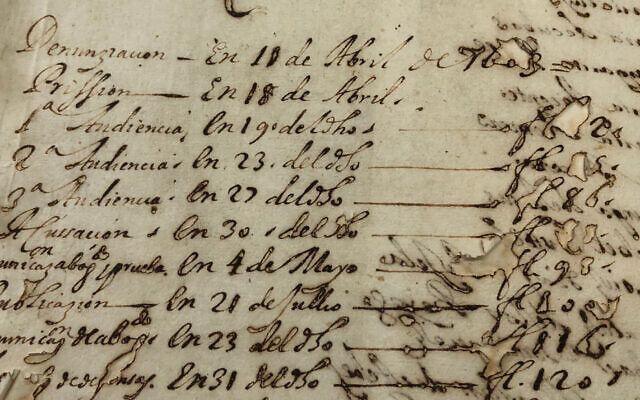

Records of the Inquisition in the Canary Islands (Courtesy of Genie Milgrom)

Milgrom told The Times of Israel from her home in Florida that not a day goes by without her receiving many requests from people asking her for help in tracing their Jewish lineages.

Milgrom’s latest project, an extensive ancestral database of family names of Sephardic Jews and Crypto-Jews, complements the Certificate of Sephardic Ancestry, enabling people to do initial research toward identifying Jewish ancestors.

Like the application for the Certificate of Sephardic Ancestry, the database was recently uploaded to the ASF Institute of Jewish Experience website.

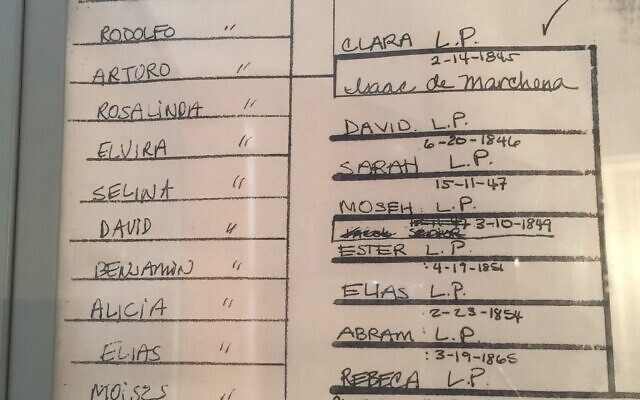

The database contains 60,000 bits of data, including 45,000 family names. There are two ways to search the database. The “Ancestral Search” option allows a user to go through 49 separate collections and look for their family name. Among these collections are the passenger list details for anyone arriving from or going to a Spanish Possession, starting in the early 1500s and continuing to 1588. Comprehensive but not yet complete, the list contains over 5,000 family names. Another example is a list of 1,430 Spanish-Portuguese Jewish names on gravestones in Jamaica from the 17th century to the 20th century. A third example is 2,657 records from the Inquisition in Mexico.

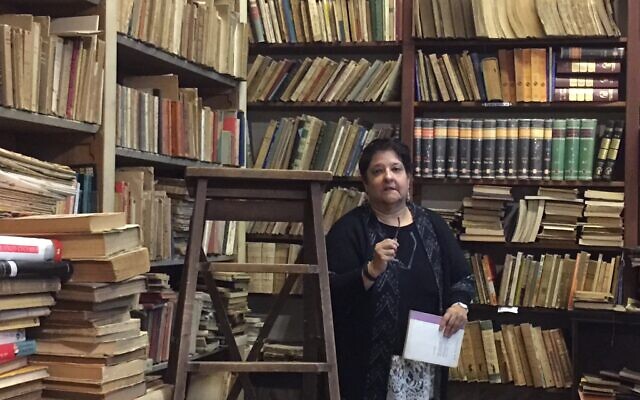

Genie Milgrom searching for rare, antique and out-of-print books in Montevideo, Uruguay. (Courtesy)

In each of these collections, the following information is supplied (where available): First name, last name, alias, year (of documentation), origin, residence, occupation, special comments, and reference (source of the information).

The second option for searching the database is alphabetically by family name, from Aabela to Zemmour. A bibliography is provided for each name so that searchers can go to the original book(s) or document(s) where the name appears and do their follow-up research.

“I was uploading the information per country, and I noticed that the same names were showing up in more than one. I needed to use a computer program that would read across all my spreadsheets and trace the progression of these names through space and time. It became evident that families mostly migrated from east to west around the globe,” Milgrom said.

Gravestone in Spanish-Portuguese Jewish cemetery in Jamaica. (Courtesy of Genie Milgrom)

Washington-area ethnobotanist Doug Schar told The Times of Israel that he has benefitted greatly from the work done by Milgrom. A researcher of Crypto-Jewish history, he learned that his father’s colonial American supposedly non-Jewish family were descended from Sephardic Jews. He was also able to connect his Huguenot relations back to Spain and to relatives who remained Jewish.

“The woman is a mad crazy data entry dynamo,” Schar said. “Her work, be it the Bevis Marks Synagogue records or the Dutch marriage records, allowed me to track my family’s movement from Spain to London, Amsterdam, and the new world. The beauty of her databases is that once you have a family name, you can track their movement around the world,” he said.

Milgrom’s database also includes links to useful auxiliary resources, ranging from a contact list for churches in Cuba where records are held, to contact information for archives around the world housing Inquisition records, to information on taxes paid in Spain on Jewish heads per village or hamlet in the 15th century, to lists of occupations found in Inquisition records from Portugal.

Family tree information on walls of a museum in Curaçao. (Courtesy of Genie Milgrom)

“When I started my own genealogical search in 2009, I had to do it all on my own. It took me three years of non-stop work. This database I have worked on for the last 10 years is meant to help people in their searches by short-circuiting the need to go back to the original Inquisition documents, which aren’t accessible online,” Milgrom said.

“I hope people will find the Jews in their family tree in the New World and won’t have to go further back than that. It will save them at least a couple of hundred of years,” she said.

To put together the name database and additional resources, Milgrom traveled the world, visiting every country with connections to Sephardic Jews and Crypto-Jews. She spent countless hours in archives, cemeteries, museums, synagogues, and rare and antique bookshops. She tracked down and poured over books with titles like, “Poverty and Welfare Among the Portuguese Jews in Early Modern Amsterdam,” “Jews in Christian Spain,” “Spanish Jamaica,” “The Victims of the Peruvian Inquisition,” and “Precious Stones of the Jews of Curaçao.”

She believes that by going beyond the Inquisition documents themselves and scouring bibliographies of scholarly works, she was able to glean “every tidbit of information.”

Milgrom’s database, which will also be available on her website, is meant to be a resource for those seeking support for their application for a Certificate of Sephardic Ancestry, and also for amateur and professional genealogists. Her website will also offer free access to documents from the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, and training videos on how to use the database and the auxiliary materials.

Names of Jews whose ancestors were expelled from Iberia appear on a memorial wall in Casablanca, Morocco. (Courtesy of Genie Milgrom)

According to ASF’s Institute of Jewish Experience senior director Drora Arussy, the certification project and database fit well with her organization’s mission to be an umbrella for all non-Ashkenazi Jewish experiences.

“Our focus is the history, culture, and customs of practicing Jews around the world. However, Crypto-Jews are connected to our people either clearly or tangentially,” Arussy said.

Certificate of Sephardic Ancestry issued by the American Sephardi Federation, Reconectar, and Genie Milgrom. (Courtesy)

“Genie’s database is a great resource for everybody, whether they know their Jewish history or not. It’s a good way to connect,” she said.

The certificate registration process (in English and Spanish) asks for the submission of information like family name, family origin, DNA test results, family trees, genealogical work completed, documentation of family customs, and photos of Jewish heirlooms. Following deliberation by an expert panel (which may request additional information), the applicant is informed whether or not they qualify for certification. For those who qualify, there is a $125 fee for the certificate and a package of educational benefits. All proceeds will go toward furthering the initiative.

“Giving people recognition and a sense of identity is meaningful. Many people, especially in Latin America, are proud of their Jewish roots,” Perry said.

Schar agreed that the certificate program gives people interested in connecting with their Jewish heritage and with the Jewish people the opportunity to take a baby step in that direction.

“Crypto-Jewish families hid their identity for hundreds of years to save their lives, and to shake off hundreds of years of hiding is no small feat. It’s a big scary move for most people,” Schar said.

“While it is not a halachic certificate, it does give people validation. And with that validation, it emboldens them to explore their Jewish heritage in a more self-assured manner,” he said.

For some people, it will suffice to learn that their last name is Sephardic, for others what they discover will launch them on a serious genealogical quest going back to 15th century Iberia. Some may want to continue living as they have been, and some may be attracted to Judaism.

“We are servicing the needs of a growing organic movement that has come out of technological advances, like social media and DNA testing. Any level of connection has a place with us,” Perry said.