This week on Times Will Tell, host Amanda Borschel-Dan takes you with her to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem for a first-time viewing of seven new contemporary art sculptures in an exhibit called Disrupted Layer.

The seven pieces were all created by artist Zohar Gotesman, who was inspired by archaeological artifacts from the museum’s collection. Much like stops on a treasure map, they are distributed throughout the archaeology wing. And as you’ll hear, some pieces blend in more than others.

There couldn’t be a better artist to take on this project: Gotesman is a graduate of Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, Jerusalem, and also holds a BA degree in Archaeology and Art History from the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Today he is also a lecturer at Bezalel, at the Shenkar College of Engineering, Design, and Art, and at Hamidrasha, Beit Berl College.

During this slightly longer-than-usual podcast, we tour the exhibit and match Borschel-Dan’s first impressions with the artist’s real intentions. Gotesman and Borschel-Dan were joined by the exhibit’s co-curators, Sally Haftel Naveh and Tali Sharvit.

The following transcript has been lightly edited.

The Times of Israel: Hi, thank you all for joining me today. Just to make sure that our listeners know who each of you are, let’s do a bit of a round and say what your name is and what your job is.

Zohar Gotesman: Hi, I’m Zohar and I’m the artist of the exhibition.

Sally Haftel Naveh: Hi, I’m Sally Haftel Naveh, and I am an independent contemporary art curator and a lecturer in different institutes in Israel. And I’m the other curator of the exhibition.

Tali Sharvit: Hello, I’m Tali Sharvit. I am one of the curators of the exhibition. My job in the museum is I am the assistant to the chief curator of the Archaeology Wing, and I’m also a researcher of ancient sculpture, mainly from the Roman period.

Six years ago, Zohar and Sally came to the Israel Museum and approached me and wanted the opportunity to be inspired from our marvelous collection of the Israel Museum. We have a huge collection of archaeology, mainly loaned from the Israel Antiquity Authority. So this collection is actually a very good place to be inspired and make new works of art.

Curator Tali Sharvit (from left) with co-curator Sally Haftel Naveh and artist Zohar Gotesman at the opening of Disrupted Layer, an exhibit of seven contemporary art sculptures inspired by the Israel Museum’s archaeology wing. (© Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by Zohar Shemesh)

As everyone can hear, we are in the Great Israel Museum, so forgive a little background noise and we are here to witness and describe to you a new exhibition called Disrupted Layer. It is my first time seeing it, so you will hear authentic responses. And I have to say, my first response was, “Wow!” I came up to the Archaeology Wing, which I have visited a gazillion million times with my kids, and the first thing I saw was a huge… what’s the size of it, actually? What’s the size of this?

Gotesman: Three meter by two and a half meter, something like this.

Okay. And it’s kind of like something that I saw recently in the British Museum, actually. And I said, Whoa, this is going to be interesting. So describe for us what is it that we’re seeing.

Gotesman: So this is relief from limestone placed on a carrier, like a construction for metal. And on the side, you have the wheel that you can carry — that modern wheel.

And my first question was actually, wait, is this where it’s actually going to be? How do we know that this is part of the exhibition? Because really, it looks like it’s propped here, about to be wheeled into the Archaeology Wing. And I understand that is intentional. So explain why.

Haftel Naveh: Yes, of course. The idea was to make this installation, to give the idea that someone was transporting kind of a new installation piece to the Archaeology Wing and just went out for a break. And we really wanted to position the first piece of the exhibition in the entrance of the wing in order to create the route or the line of the exhibition and let the people understand that we have a contemporary art exhibition in the archaeology wing, as well as to make a connection to the other just positioned wing, which is the contemporary art in the Museum of Israel.

Zohar Gotesman, No Relief, 2022, Halila limestone, metal frame, and pallet jack, 218×405×100 cm. (© Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by Elie Posner)

Now, I have to say, because I’m not an artist or an archaeologist or play one on TV, I looked at this and at first I was wondering, actually, is this new? Is this old? Because it really has the themes of the Great Gates of Ishtar and things like that. So I assume that was intentional.

Gotesman: Yes, this was intentional. Actually, it’s a quotation that I made some changes in it — a lot of changes. First of all, I took relief from the palace of Sanchariv from Nineveh, ancient Mesopotamia, and in the original, it’s a series of reliefs in the corridors that is depicting quarrying of a large, huge stone and making a lamassu sculpture out of it and dragging it into the entrance of the palace and placing it there. I just took part of it and made a crop, cropping according to what I want. This is the original depiction. And then instead of hundreds of slaves with the people who are forcing them, I took away everybody and left only one. This one is trying to carry the huge weight with a rope. And of course, for him, it’s not possible to carry the huge lamassu. I just have to explain what a lamassu is.

Sharvit: The lamassu are actually fantastic beings. Their sculptures, their huge sculptures were positioned in pairs in the entrances of the palaces and the special rooms inside the palace, like the throne rooms, and they were protecting the entrances. And this is why we chose to exhibit this sculpture here. In the entrance to the archeology wing as we sort of try to take their anthropomorphic power to their new place.

Okay, so let’s dive in. Let’s go further into the exhibition.

Zohar Gotesman, Good Morning Sunshine, 2022, Limestone and pigments, 200x150x25 cm. (© Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by Elie Posner)

Oh, wow. Okay, we’ve reached the second, wow. Wow! Okay, so wow doesn’t describe anything but my amazement and essentially what I see — and then you can tell me what the intention is — is a skeleton, a human skeleton that is undergoing excavation, shall we say. You can see the strike marks of the tools that would have excavated it. And surrounding it are all sorts of different skulls from creatures such as, I don’t know, it looks like even maybe crocodiles or even dinosaurs, I don’t know. And maybe other human skulls and some ancient tools that look to be next to it also. But for me, as just a regular person, it looks like it’s modeling an excavation of a tomb. Am I anywhere close to what your intention was, Zohar?

Gotesman: More or less, actually, it’s a very big limestone block that I carved into it. Shapes of a human being that is lying inside a kind of futuristic fossil. Around it, I placed lots of skulls of animals, real animals, but this is carved, and they are animals which are extinct now in the Red List. And you can count them on your hands, how many are left in the world. Examples for the animals. You can see Okapi or Sumatran rhinoceros or dolphins from the Ganges River, like elephant, forest elephant, and lots of others. I could have made thousands more and made it bigger and bigger and bigger.

I have to say that we are now in the prehistoric wing. It tells a story of 1.4 million years of evolution that was from excavations in Israel, remains that we’ll find here, from the early Paleolithic age till the Neolithic till and then we go out of here.

And we should remind our listeners that Israel was a land bridge. And so it’s actually very rich in this kind of finds and very important in terms of research.

Now I want to ask you something. The humanoid, I don’t know if it’s meant to be us or an earlier man is resting with his hands crossed on his chest in the very typical inside-the-grave kind of posture. What does that mean to you?

Gotesman: Yes, as you can see in this section of the archaeological wing, we can see a few examples of human burials together with animal bones, animal offerings. I took from this inspiration towards this sculpture and placed — the sculpture is located next to the exit of the gallery — and you can see that all of the other graves are horizontal. I took the stone and make it perpendicular. I mean, it’s vertical. And to place it in front of our eyes to state something, it’s as if, like a vampire is coming out [of his grave].

I actually thought of that because of the crossed arms as well. You see that in all the vampire movies.

Gotesman: Vampire or King Tutankhamun, that is. So it’s like a symbol of, the crossed hands are a symbol of in the ancient times, of a kind of sleep that you know that it will be awakened at night.

Okay, a little freaky. Glad we’re here during the day.

Gotesman: Yeah. But as he is living forever, around him are skulls of animals which are dying out today.

Right. Very sad. Okay, yalla, let’s move on.

Zohar Gotesman, Rise and Fall, 2022, Basalt, 90×53 cm each. (© Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by Elie Posner)

Okay, so what we see now, I think also displays Israeli humor. To me, it looks like a game we have here in Israel called Nachum Takum, which is basically a punching bag with a little figure that you hit it and comes bouncing right up. You hit it again, comes bouncing right up. That’s what it looks like to me. But they’re obviously carved out of stone and they look very, with ancient motifs in terms of how it is carved. So again, let’s hear what it was really meant to be.

Shavit: Well, the first association you had is correct. These two basalt god and goddess are made to be looking like the toy of Nachum Takum. And they’re made of basalt because as you look around this gallery, you see that most of the objects here, the large ones, are made of basalt and they are from Israel, from the time of the Bronze Age in Israel, and actually the late Bronze Age of Canaanite in this period. And Zohar looked around and quoted motifs and decorations and facial features of the little sculptures or figurines made of basalt, made of pottery that are shown around. And all of them are related to the cultic practices of the period. And this mixture is combined here as new figures, the one that he created. And maybe you want to say something about these creations.

Gotesman: So imagine for yourself what is the most scary thing that you can have in a museum of archaeology?

I think it was your previous sculpture.

Gotesman: But here we go to a new level of scariness. You have two sculptures, each one is 400 kilos next to glass vitrines full of very important archaeological remains. And furthermore, I will say that they are leaning on one point. Each one has only the base, [a] round base. So I wanted to create this tension. In all the area we have the phenomena of tel mounds, archaeology mounds, which is settlements that have been repopulated again and again. Thousands of years of repopulation, one on top of the other. And then you build a kind of layered cake of cultures. One culture is rising, one culture, and then on top of the other one, which fell down, falling and reappearing. But ideas — ideas can last and remain for ages. Ideas about culture, about gods, about language. The tree that you create, a line that is stretched from thousands of years back, even till our time with different changes.

Okay, so interesting. Yofi. All right, let’s head on. We have more to see.

Zohar Gotesman, Final Escape, 2022, Lebanon cedar wood, found camel bones, pigments, lapis lazuli, rubies, and gold leaf, 176x84x163 cm. (© Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by Elie Posner)

So we were just saying on our way to find this torture device it looks like, that basically, we are playing hide and seek in the archeology wing and finding all of these really interesting sculptures. Now, this one, I have to say, really does look like an electric chair to me, made out of wood with some, I don’t know, maybe it’s more like a control center because it also has a helmet and maybe it’s a cockpit and maybe — I don’t know what it is, actually. So let’s hear what it’s supposed to be.

Gotesman: Okay, so this is a sculpture till now we had some stones. Now we go into wood, in special wood. The wood is a cedar. Cedar of Lebanon from the Bible, from the temple. What is depicted here? First of all, we are in the area of the Iron Age, 3,000 years ago, the kingdom of Israel and Judea.

Ah, so therefore a throne, right?

Gotesman: Yes. This is a throne that is being hybrided with an F-35 ejection seat. It is a kind of torture device. I tried to reconstruct this kind of throne that used to be, we tried to create it as if it was a throne from the past inlaid with all kinds of ivories.

Which we just heard about a find this year in the City of David, about ivories inlaid on chairs. Very interesting.

Gotesman: Exactly. So the beginning of this project, this sculpture, the main point is the vitrine. There is a vitrine there that is depicting lots of ivories from Samaria. And in the Bible, Amos, the prophet Amos is talking about the ivories in beds and in the chairs and in palaces of ivories as a symbol of corruption.

Right. Too much luxury for the people of the time.

Gotesman: It was very expensive. It was inlaid all over the walls also. So, what I did, instead of taking ivory and dealing with the corruption idea in ivory, I took camel bones that I found in the desert and made lots of quotations to that time. In the front, you can see on the… how do you call this?

I don’t know, maybe a footstool?

Gotesman: On the footstool of the king I placed a helmet also from wood. Lots of gold on the helmet, which is laying on the side and burnt. By the way, I burned everything. From the background, you can see layers of burning as reminiscences of a kind of catastrophe that just happened. You don’t know who is the guy sitting on the throne. Is it the king? Is it the pilot? If the king sends the pilot somewhere, if he’s coming back or not?

Haftel Naveh: We can also say this is a kind of Machiavellian allegory to the disturbing behavior of a king, corruption. We can also see the piece as some reference to nowadays. As well as other places. It’s universal.

Okay, let’s move on.

Zohar Gotesman, Sounds of the Syrinx, 2022, Carrara Statuario marble, 135x60x40 cm. (© Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by Elie Posner)

Okay. We have found our new friend, and we are in the Roman period, it looks like to me. We walked quite a bit from the previous exhibit, which is kind of a testament to how large this wing is and really, really fun to visit here. So this guy, more than any of the other ones, in my eyes, really kind of blends in. And if it were not for a slightly different color and the very orange words describing what this is, I would think it was almost part of the time period.

Haftel Naveh: I want to say something about blending in. The whole idea of the exhibition was to try to install the seven monumental pieces into the collection, the permanent collection, in order to create this blending. I mean, not creating this attachment, but just to create this integration, in order to create a real dialogue and raising really interesting questions regarding the relationship between the two disciplines, archaeology and contemporary art. So that was basically the idea.

So just to describe this guy a little bit, it’s kind of a cupid-looking young fellow who has a gazillion million tentacles coming out of him, it looks like, to me. Or roots or something like that. Or vacuum cleaner tubes. Who knows? And do I spot a little ship inside as well? So what is the intention here?

Gotesman: As you see on the left, like an ancient Roman sculpture from Caesarea, found in Caesarea of a satyr. We are all around us. We have Dionysus who is accompanied by satyrs in different sculptures here, copies, Roman copies of earlier times. I was very impressed by that sculpture, of the satyr. For me, [it is] a masterpiece, so I decided to copy it. It has all his limbs and other places, other parts are missing, broken. In my mind, in the middle of the night, I imagined them reappearing, coming to life and reconnecting, but not in the way it was, just in the way I wanted to be. So I started out of all the broken limbs, [the figure] start to reappear, kind of, you were right. You don’t know what it is. Is it an intestine? Is it a cord? Like a vacuum cord? Is it a vine? Is it a snake? I’m not sure. What I know is they start to reappear from different parts of broken, different elements that were broken and make a kind of metamorphosis and unite together. I think there are two or three that combine and start as a huge lump of spaghetti to choke this satyr and to start to get to start to close all over him.

What is going into his mouth? It looks like it could be a straw or for, I don’t know, bagpipes or I don’t know.

Gotesman: I also don’t know. What is this at the end, where it comes from and where it goes? It’s like kind of the same serpent goes everywhere.

Shavit: Actually, what Zohar is doing here is an echo to something that actually happened in the Roman times, when Roman sculpture copied and emulated the ancient Greek sculpture, and when the original Roman sculptor copied the original, he took freedom and added some things and changed some things. And Zohar takes it to the limits. He actually creates a new creation.

Right. And what is all sculpture but just the copying of us? And we’re all copies ourselves, right?

Shavit: Indeed.

Yofi.

Zohar Gotesman, Them, 2019-2022, Four sandstone plates, 53x40x8 each. (© Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by Elie Posner)

Okay, I almost walked right by this because I don’t actually know what is new and not here we are in the Middle Ages room, I believe, which is really a fun room to visit because it has a fresco that is really fascinating, and it has all sorts of very interesting Islamic things as well. Now that I said Islamic, I’m going to guess that what is new in this is right in front of me with the three shields — and I’m wrong. All right. What is new here?

Obviously, the demon-looking things, because we’re talking about Zohar’s mind here. Okay, so we have four reliefs with demonic influences and also maybe some Christian influences with the baby Jesus, I don’t know. In the center of at least two of them. I’m not sure if it’s meant to be a series, if they’re connected. And if so, do they go from right to left? I would imagine right to left, not left to right. So let’s hear it. Limestone again?

Gotesman: It’s actually sandstone from Europe, from Czech sandstone. We are now in the Crusaders area, so I took the liberty to get into the mind of a Romanesque sculptor or Crusader sculptor and made four reliefs that are depicting four racist remarks that keep reappearing in all humanity. One of them is — we call it Them. — so they come to eat our babies, our baby. They come to rape our women. They come to rape or to kidnap. They come to spread disease, and they come to take our money.

So it’s basically about antisemitism.

Gotesman: Not necessarily. What I thought is that these were remarks or things, stereotypes said about Jewish people in the Middle Ages.

For sure. Or today.

Gotesman: So I wanted to deal with it in a different way. If you take [the] double negative when you sculpt this kind of racist remark that is found, it keeps appearing, you create it as ridiculous. How can it be like if everybody is saying about it for sure is bullshit. Can I say bullshit?

Yes, of course. So essentially it’s “them” because it is not us.

Gotesman: Yes. It’s a fear of the other.

Haftel Naveh: I will also say that the style, the reliefs are carved also very grotesque. And in a way, this is like canceling this very serious remark to the other or this fear. So by appearing and using this kind of aesthetics, you are also kind to try to ridicule it or laugh about it.

Right. They look like Gargoyle kind of faces or things you would see on churches in Europe.

Haftel Naveh: And also you can see Zor kind of quoted the aesthetics and the symbols of many of the pieces here in this gallery of Crusader time. Because the Crusader period is based on the aesthetics of the Romanesque. So it’s kind of a quotation of different items here in the gallery.

Let’s remind our listeners that the Crusades were a holy war to eliminate the other.

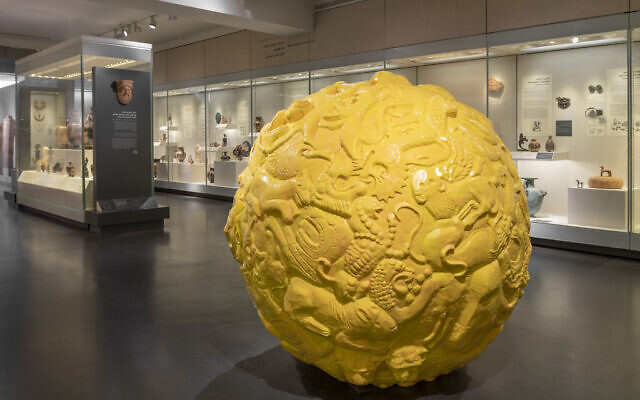

Zohar Gotesman, Foothold, 2022, Polymers and pigments, diameter: 160 cm. (© Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by Elie Posner)

Now, forgive my historical ignorance, but we just went from the Middle Ages to early Greek, and I think we kind of went back in time, didn’t we?

Shavit: We are actually in the galleries dealing with neighboring cultures. So we just finished the route taking us through the land of Israel, and now we are in different places, and we are standing in the crossroad between Roman archeology and Greek archeology and Mesopotamian archaeology.

Okay, so let me describe what I see. It seems like a big yellow ball of trouble. We have a whole bunch of grotesque, ridiculous features, such as demon-esque-looking lions. And we have fish-eating snakes. And we have I don’t know, I would call it the Gilgamesh, maybe Gilgamesh’s flood with everything. Everything that’s not being saved by Noah’s Ark just got eaten up by this big ginormous ball about a meter and a half that is yellow like the sun. So what are we seeing here?

Gotesman: I imagined a little child taking this yellow rubber ball, throwing it in the corridors of the museum, and this yellow gooey ball starts to collect what will stick.

Is this made out of rubber?

Gotesman: This is rubber.

Wow. I didn’t know. It looked like painted plaster or something, but rubber. Wow. How do you make that? You have to build a cast and then fill it with rubber?

Gotesman: You have to sculpt it from clay made into the negative, schmear it with silicone and then build it from the outside in.

Wow. Brilliant. And so there’s a seam somewhere.

Gotesman: Somewhere, yeah. So what this rubber ball collected is all the depictions of lions that are in the collection. More than 100 depictions of lions from thousands of years back [up to the] 19th century, but most of it is from the ancient archeology collection.

But is that a fish that I see there?

Gotesman: No, all lion depictions.

It’s a very fishy lion.

Gotesman: So what I try to do is to take from different times, from different depictions, different sizes, like from a tiny coin till a lion block from basalt, put everything together in one shape. Everything together in one color, in one material, and see if they can live together.

The great equalizer. Yellow rubber.

Gotesman: If you put everything together, mix. It’s as if when you see animation and the cat and the dog and the mouse are fighting, you see a ball with arms and legs. This is it.

This piece definitely does not blend in. Do you have thoughts on that?

Gotesman: Till now we had, I say, real materials used in the time period that is blending in. If you had the area of the Bronze Age, you had lots of sculptures and artifacts from basalt. If you went to the early Stone Age, you had stone. So each one is real-ish material. And here we wanted to make a statement with something that never will blend in. The color is bright yellow with a dark background. So it’s kind of creating a kind of tension or some sort of dangerous feeling.

You do not want to get behind this if it’s rolling around.

Gotesman: And no kicking because it’s massive. So then what we wanted to do is if you go from far away, you start to see this tiny yellow spot in the background. You get closer and closer, and it starts to become big and huge and scary. As if the boulder of Indiana Jones is rolling towards you. Then it creates a kind of strange connection to the surrounding, which is totally different. And this is the grand finale of the exhibition.

Wait, this is number seven? I didn’t even realize it. Wow. Okay.

Gotesman: This is the explosion. The sun exploding.

Curator Tali Sharvit (from left) with artist Zohar Gotesman and co-curator Sally Haftel Naveh clown around next to the first of seven contemporary art sculptures inspired by the Israel Museum’s archaeology wing. (© Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by Zohar Shemesh)

Wow. Okay, so let’s talk a little bit about the exhibition in general. Now, it just opened, right? So you haven’t heard much audience feedback, I would imagine, but to me, it is just so powerful and fun. And fun is something that you don’t always feel when you come to a museum, and maybe perhaps, especially to the archaeology wing. But I just felt like I went on a little treasure map journey and it was just the greatest pleasure. Was that also part of the intention?

Shavit: I think it is, really is, because this is the first time that we exhibit exhibitions of contemporary art in the galleries of archaeology and the permanent galleries. And one of our motivations were actually to refresh the visit of our visitors, to welcome different visitors who haven’t been coming to see archeology, per se, and have a new opportunity for new visitors. And I’m really happy to hear that you had fun looking at it. Because this was the main idea, to do something different, to do something with a different color.

We’re staring at yellow here, guys, a different color. Let’s talk a little bit about the technical side of it. Now, I noticed that all of the writing, all the captioning for the exhibit is in bright orange because you want to blend in, but yet you want it to stand out. So how long did it take you guys to decide on that?

Haftel Naveh: Well, actually, there was something that came along right from the beginning, this kind of intervention or kind of relationship between archaeology and contemporary art. It’s quite popular for many centuries already. But our idea was to interfere in the galleries of the archeology wing in order to create this very profound dialogue. I mean, I think by choosing the ancient materials, ancient techniques — besides the huge rubber ball — we’re trying to assimilate into the collections. And by creating this limit between contemporary and archaeological items, we would really try to challenge the perspective of the visitor and make him think a little bit about the difference between the disciplines and times. Because I think, in a way, what Zohar really does here very well is recollecting techniques, materials, aesthetics, and ideas from ancient times in order to say something about nowadays. So this kind of relation between past and present, ancient and modern and contemporary, was at the main heart of the exhibition. So we couldn’t just go for a regular format of presenting pieces along together, like in a gallery, but it had to be inside of the permanent exhibition.

Okay, Zohar, back to you. Now that you see everything in place and it’s been six years, this project has been six years in coming, is it fulfilling your personal expectations that you had from yourself?

Gotesman: Well, I am always harsh on myself. But I think yes. It was a long and amazing journey, and I learned a lot with those two great curators and the other curators of the archaeological wing. But yes, and every time I come here, I keep gazing, staring at all of the amazing collections and I want to be influenced more and more by it. It’s just this neverending affection and love.

Wow. Amazing. Thank you, all three of you, for taking me on this whirlwind, wonderful tour. I so appreciate it. And I recommend everyone come out and see this amazing exhibit.

Times Will Tell podcasts are available for download on iTunes, TuneIn, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, PlayerFM or wherever you get your podcasts.