At first, Rabbi Yoni Rosensweig was just looking for some answers to a few questions he’d been asked about Jewish law and mental health. That quickly turned into a book and then a center, which he helps run and which has already trained dozens of rabbis.

“This topic kind of chose me. I fell into it and I realized that there was what to do. And before I knew it I saw that there was a significant response from the community. So I said to myself, if this is so important to people, maybe I should be doing this,” Rosensweig told The Times of Israel on Sunday.

Though he is primarily focused on this nexus of mental health and Jewish law, Rosensweig wears many hats. Ordained by the Orthodox Yeshivat Birkat Moshe in the Maale Adumim settlement, he leads the community of Netzach Menashe in Beit Shemesh, teaches at the progressive Orthodox Midreshet Lindenbaum in Jerusalem, has written several books, and maintains a significant following from his work as a posek, a rabbi who makes practical rulings on Jewish law, or halacha. His ask-me-anything sessions ahead of Passover, for instance, are not to be missed. (Full disclosure: He also officiated this reporter’s wedding in 2019.)

Rosensweig’s journey into the field of mental health began roughly five years ago when he received some questions from his community. Looking to better understand the topic, Rosensweig spoke to Dr. Shmuel Harris, a psychiatrist and the head of Machon Dvir, a behavioral health clinic in Jerusalem.

“My goal was to just answer a few questions. But as I got into it and realized that there’s a lot more work to do here, we decided to write a book on this topic,” Rosensweig said.

Get The Times of Israel's Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories

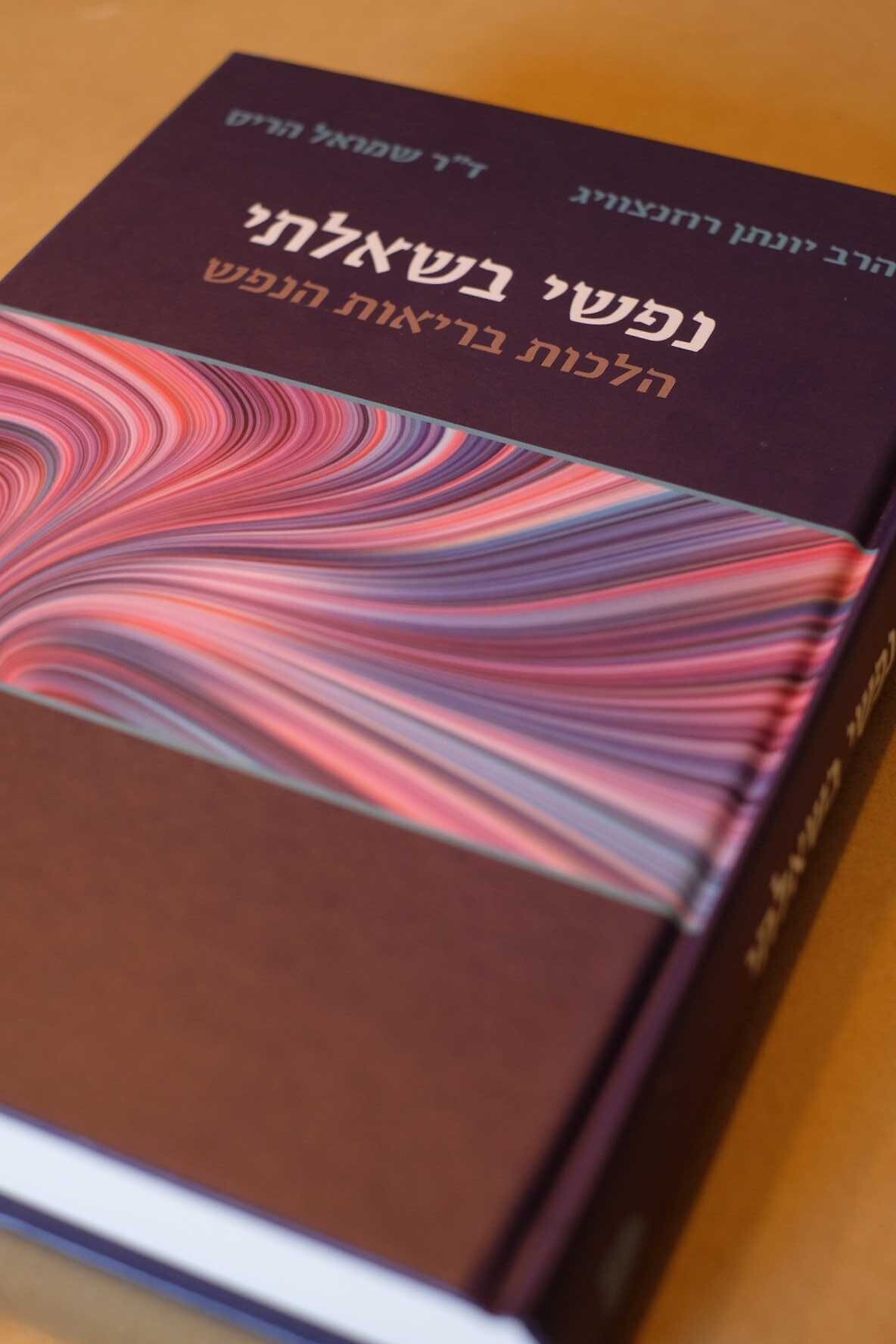

The book that the two wrote together, “Nafshi B’She’elati,” was released in Hebrew by Koren Publishers in 2022. An English translation is only expected to be published later this year, but his work has already made waves in English-speaking communities in Israel and around the world.

“There are many topics in halacha that I could have chosen to look into. But this one affects hundreds or thousands of people every single day. It’s actually unbelievable to me that a book like this hasn’t been written before. It’s something that’s so monumentally important to people, that directly deals with their quality of life and sometimes with their very lives,” he said.

The 512-page “Nafshi B’She’elati” is geared toward rabbis and other professionals, with detailed explanations of technical terminology — both psychological and rabbinic — and footnotes that are often longer than the main text. But even for casual laypeople, it is still a fascinating read, addressing topics like schizophrenia, depression, eating disorders, phobias, autism and dementia.

With the release of the book, Rosensweig also founded Ma’aglei Nefesh: The Center for Mental Health, Community, and Halacha, which helps connect people with mental health issues to therapists and rabbis, produces literature on mental health and halacha, and performs 50-hour training sessions for rabbis on mental health topics.

We know how to talk about cancer, not depression

Though he is far from the only rabbi to consider the connection between mental health and halacha, Rosensweig has emerged as a prominent voice on the topic, speaking about it at least a week either within religious communities — in synagogues or seminaries — or to medical or mental health professionals, in hospitals, or to groups of social workers.

Rosensweig held such an event on Sunday night, speaking about his work in the Neve Habaron Synagogue in the northern town of Zichron Yaakov, where he was joined onstage by a religious woman who shared her experiences dealing with anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts.

The talk dealt both with the need for communities to expand their thinking about mental health and with what considerations go into his rulings on halacha.

Rosensweig said his hope is that through events like this, communities will learn the vocabulary necessary for open discussions about mental health, as they already have for physical health.

Or discusses her struggles with mental health at the Neve Habaron synagogue in the northern town of Zichron Yaakov on January 22, 2023. (Judah Ari Gross/Times of Israel)

“Even if you don’t have professional, medical training, you can make small talk about physical health. If you find out a person — heaven forbid — has cancer, someone will say, ‘Have you seen an oncologist? Have you started chemotherapy?’ I don’t know what chemotherapy is, not really, but I can still talk about it and sound sensitive and informed so that the person feels that they can talk to me about it. If I run into them on the street, I can ask how they are doing, how they feel,” Rosensweig said.

“But when it’s depression, we don’t know what to say. That’s the problem. I know that five years ago, I didn’t know how to have that kind of small talk about mental health. If you find out someone has depression, you often don’t know what comes next. Do you see a psychologist? A psychiatrist? A social worker? How long does it last? What’s the process? And if you see that person, what do you ask, ‘How’s your depression?’ What’s the right and sensitive thing to say?” he said.

Halacha and mental health

For religious Jews, halacha governs most aspects of their lives, such as how and what they eat, how they interact with family, and how they spend Shabbat. Those religious laws can be challenging or even dangerous in some cases for people with certain mental health issues. Fasting on Yom Kippur can trigger a potentially grave relapse for a person who has dealt with an eating disorder, for instance.

A copy of Nafshi B’She’elati by Rabbi Yoni Rosensweig and Dr. Shmuel Harris. (Judah Ari Gross/Times of Israel)

“Nafshi B’She’elati” and much of Rosensweig’s work focuses on delving deep into the source material to find which aspects of halacha are flexible, where exceptions can be made, and which are unequivocal divine prohibitions that can’t be superseded. Some of this is based on the nature of the commandment — does it come directly from the Bible or was it developed later by rabbis — and some is based on the effect that it would have on the person — is it life-saving or merely palliative?

However, while much of “Nafshi B’She’elati” deals with issuing halachic leniencies for people with various mental health conditions, Rosensweig stressed that rabbis should not be blindly permissive either in order to ensure that the person feels that they are still abiding by Jewish law and are still part of a religious community.

He noted that no one is forced to follow Jewish law. The people coming to him are not looking to get out of religious obligations; they want to follow them.

“People want to fast on Yom Kippur. If you tell them they can’t, they feel rejected from the group, from the community. They want to be part of this holy and awesome day. When someone’s told they can’t fast, it’s not good news for them — it’s difficult news,” Rosensweig told the three dozen or so people who gathered in the Zichron Yaakov synagogue.

Rosensweig offered an example, a relatively common one, of a person with depression or anxiety who is helped by listening to music. What can a person like that do on Shabbat, when the use of electricity is restricted?

In theory, Rosensweig said, a rabbi could simply permit such a person to use their phone or computer to listen to music on Shabbat. However, doing so would not necessarily make the person feel that they are keeping the laws of Shabbat.

“We’re trying to fight stigma. We want people dealing with mental health issues to feel seen and understood, not to feel that they are separate from the group, that they are rejected, that they are second-class. Every exception made for a person for mental health reasons feels to them like a failure, like they are not really keeping Shabbat, that they are not strong like everyone else,” he said.

Instead, he recommends having the person put on a playlist on a loop before Shabbat so that if they need to listen to music, they need only put in their headphones without actually turning anything on.

“You need to strike a balance in how you rule on halacha,” he said.