China's Demographic Dilemma: Balancing Urban Growth and Birth Rates

China grapples with declining fertility amid urbanization push. Experts warn of conflicting policies as the nation seeks to boost birth rates while encouraging city migration, potentially exacerbating population challenges.

China's demographic landscape is undergoing a significant transformation, with the government pledging to create a "birth-friendly society" while simultaneously promoting urbanization. This dual approach has sparked concerns among demographers about potentially conflicting objectives.

Mary Meng, a 37-year-old mother working in Shanghai's tech sector, exemplifies the challenges faced by urban parents. "The work pressure is such that you don't even have any time to spend with your child," she explains, highlighting the difficulty of balancing career and family life in China's bustling cities.

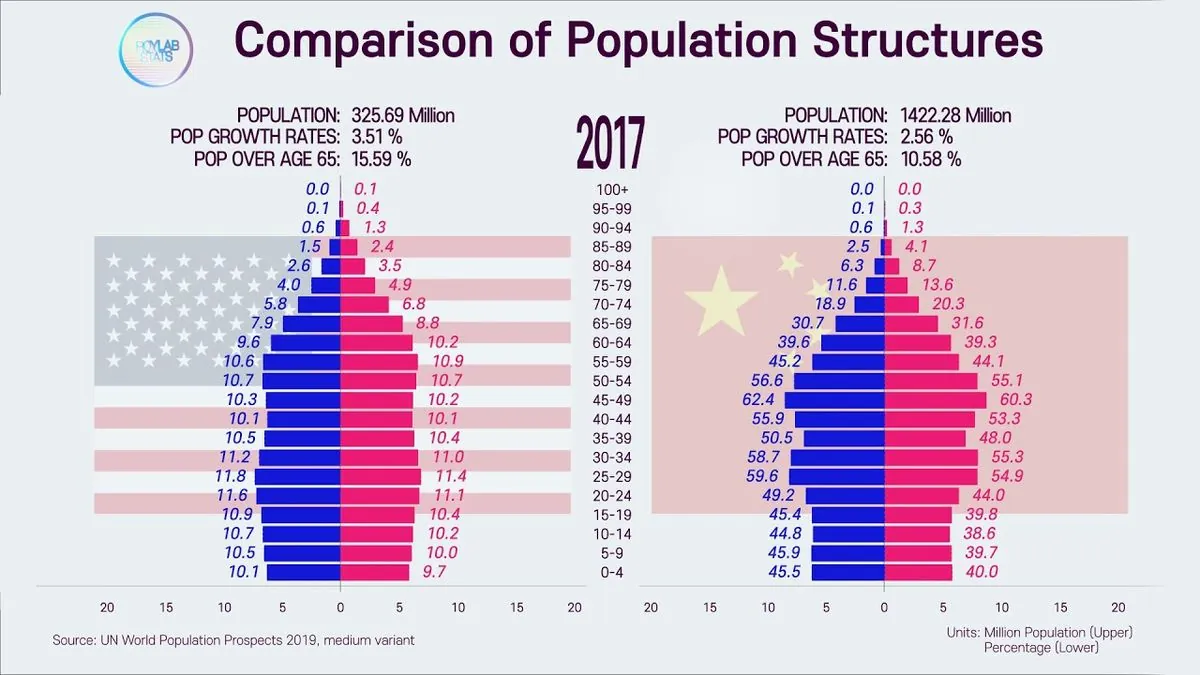

China's population peaked in 2022 at 1.4 billion, and the UN projects it could fall to 767 million by 2100. This rapid decline is compounded by the fact that China's working-age population has been shrinking since 2012. By 2050, it's estimated that one in three Chinese will be over 60 years old, presenting significant economic and social challenges.

The government's recent political gathering outlined plans to implement measures long advocated by population experts, such as reducing childcare and education costs. However, these efforts are juxtaposed with a push for increased urbanization, which aims to stimulate housing demand and economic growth.

Demographers argue that this urbanization drive overlooks fundamental demographic principles. Urban environments typically lead to lower birth rates due to factors such as high living costs, limited space, and work-related stress. In fact, China's couple infertility rates have risen from 2% in the 1980s to 18% today, surpassing the global average of 15%.

The disparity between urban and rural fertility rates is stark. In 2020, rural areas reported a fertility rate of 1.54, compared to the national average of 1.3. Shanghai's fertility rate in 2023 was a mere 0.6, less than half the national figure of 1.1.

Yi Fuxian, a demographer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, criticizes the approach: "The suppression of fertility rates by population density is a biological law." He argues that driving young people to "birth-unfriendly big cities" will exacerbate the aging crisis.

This phenomenon is not unique to China. Other East Asian countries like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan experienced rapid post-World War Two urbanization and industrialization, coinciding with some of the world's lowest fertility rates.

"I don't have the money or energy [to have children]."

However, China's relatively lower urbanization rate of 65% (compared to 80-90% in Japan or South Korea) may offer some flexibility. Experts suggest that improving rural living standards through better public services and land rights reform could have a more sustainable impact on both economic growth and birth rates.

Samir KC, professor at the Asian Demographic Research Institute at Shanghai University, emphasizes the importance of population size as an economic multiplier. This underscores the need for policies that effectively balance urban development with fertility goals.

China's "birth-friendly society" vision includes reducing parenting costs, extending parental leave, upgrading healthcare, and increasing child subsidies. However, demographers argue that successful birth policies, as seen in countries like France or Sweden, also require greater gender equality, stronger labor rights, and robust social welfare systems.

Yun Zhou, a demographer at the University of Michigan, cautions that focusing solely on reducing childcare costs "promotes a certain set of family values that demand that women take domestic responsibilities."

As China navigates these complex demographic challenges, the key to success may lie in creating an environment where citizens like Mary Meng can envision a brighter future. "Now everyone thinks there is no prospect at all," she laments. "No matter how hard you work, it is just survival."