Georgia's path to EU hits roadblock as hundreds face arrest in Tbilisi

Pentagon alerts: New Russian super-missile might strike Ukraine within days

Democrats push for last-minute changes to US immigration policy before 2025

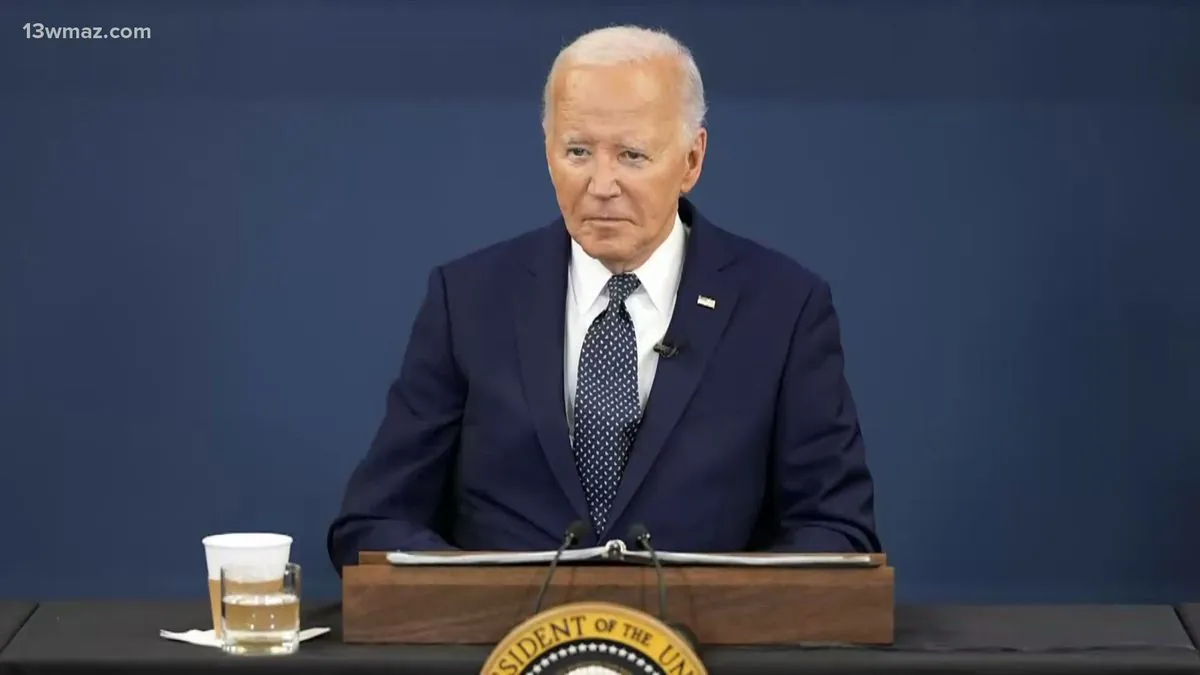

Biden talks big money and future of women's health at White House meeting

Trump's unexpected trade strategy leaves world markets guessing what's next

Lithuanian defense chief warns: Europe must pay its fair share for protection

Ex-mayor's secret past leads to major international spy scandal in Philippines

Small-town mayor's true identity leads to international spy scandal in Philippines

Argentina's economy shows signs of life as inflation drops to unexpected lows

British farmers bring tractors to London streets over new tax rules

Hungary and Slovakia scramble to keep Russian gas flowing after bank sanctions

Capitol arrest sparks different stories about Rep Mace encounter

British health system makes unexpected move on youth gender care treatments

Trump's solo trade plans worry global markets as key advisor stays away

Russian army gets dangerously close to key Ukrainian industrial city

Disney community mourns after sudden loss of popular content maker at brand gathering

Secret memo shows how US plans to deal with unusual four-country partnership

US wildlife officials finally take action to save disappearing monarch butterflies

Haiti's main airport makes comeback while medical help returns to streets

Military showdown in Somalia's south: Two forces clash over power dispute

Last stand: Top diplomat faces tough questions about Afghan exit

Romanian parties join forces to stop far-right rise in power struggle

How frozen Russian money could save Ukraine when Trump returns to power

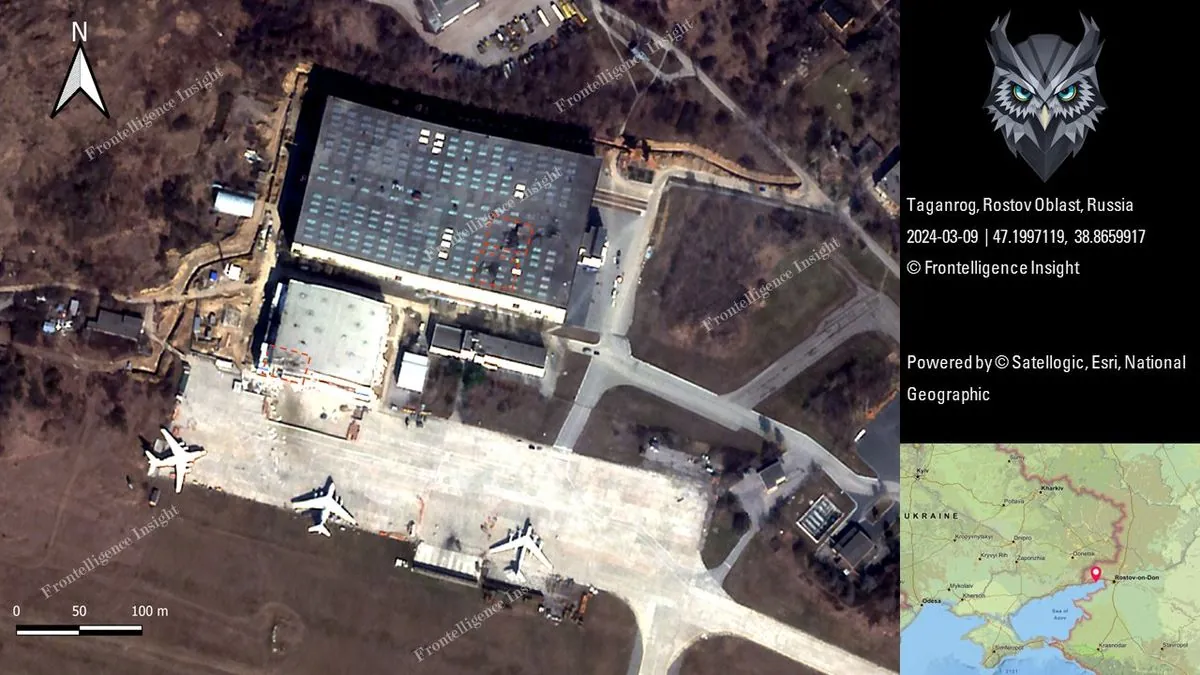

Russian military base hit: US missiles cause stir in southern region

Poland pushes for huge EU defense money pool as Russia worries grow

Small Austria shows big differences with US: What Vienna can teach America

Syrian refugees in Europe face uncertainty after Assad's sudden departure

EU prepares new round of restrictions on Russian shadow fleet and allies

Washington Post's veteran editor gets game-changing role in political coverage

Indian tycoon drops major US port funding request after legal troubles

Senior Taliban leader dies in Kabul mosque blast - what's behind this attack?

West African military rulers shake up mining sector with tough new demands

Strange disease outbreak in Congo: First lab results point to unexpected cause

Belarus court sends reporter to prison over critical coverage of state affairs

Capitol Hill handshake leads to unexpected arrest of foster care advocate

Wall Street experts show how Trump's trade plans might shake up your money in 2025

What a small European country shows about modern American problems

Global money game: How frozen Russian cash could save Ukraine's defense plans

French leadership puzzle: What's next after prime minister's exit?