"Social disruption caused by pathogenic diseases, as clearly demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic," the authors wrote in a study released Monday. caused by climate change.

Dr. Aaron Bernstein, director of the Climate MD Program at the Center for Climate, Health, and Global Environment at the Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University, sat down for ABC News' Start Here podcast. I was. Learn about our findings and their far-reaching implications.

Let's start here: Dr. Bernstein, can you explain what you've learned from this study? How does climate change relate to things like COVID and monkeypox?

BERNSTEIN: Good question, Brad. Climate change is implicated in nearly every infectious disease we can imagine already knowing. But it's also true that pre-2019 he's also important to things we haven't seen yet, like COVID-19. That's because diseases like COVID and HIV, which first emerged, are usually viruses that bring animals to humans.

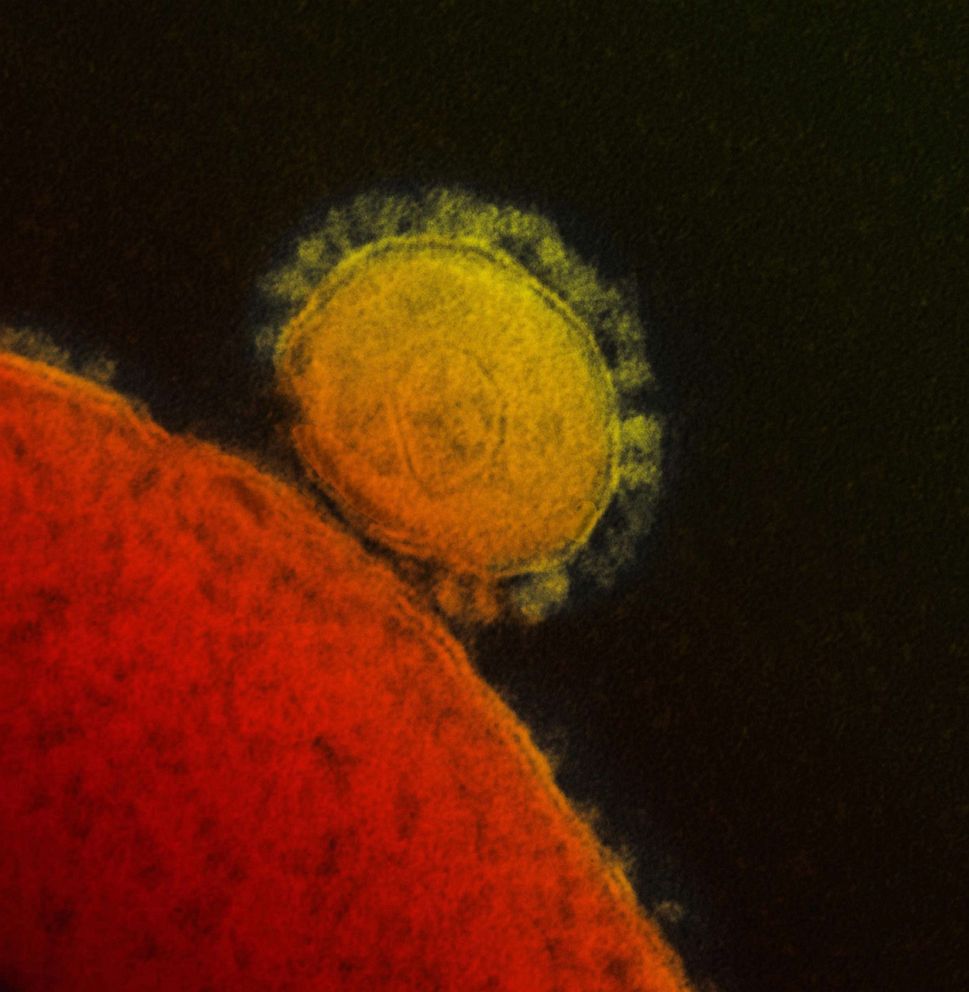

Coronavirus.

Callista Images/Getty Images

mosquito. It's natural for people to bump into animals, but animals can also bump into other animals. And what climate change brings is escaping the heat with everything you can head for the hills and poles... sort of like a bumper car juggernaut. Animals that have never touched each other bump into each other, trying to escape the heat.

So he has two problems here. One is how more intense heat events, changes in the way rainfall occurs due to climate change, will affect the diseases we know. And how this bumper car issue affects new things coming out in ways we really don't want to see, and we may be seeing an unfair share lately.

Start here: I'm trying to figure out what pathogen this affects. I think the study said that 58% of [the world's infectious diseases] will get worse. Are you saying that more than half of the viruses on the planet will get worse in the next few years basically because of this?

BERNSTEIN: They looked at all pathogens, not just viruses. I mention viruses because, like COVID-19 and HIV, they tend to be ugly surprises. But they saw bacteria, fungi. Again, what they wanted to answer was, will climate change look like it's going to be overall worse or overall better for the infectious diseases we know?

There are certainly some diseases, and malaria is a good example of that. Malaria has been in West Africa forever. It's been there for so long that the human genome evolved to deal with the parasite, in the form of sickle cell disease. It is a disease in which red blood cells react and look like sickles.

Glaciologists Andrea Fischer (L) and Violeta Lauria of the Austrian Academy of Sciences walk

Kerstin Joensson/AFP via Getty Images

Two defective copies of the gene result in sickle cell disease. But one copy actually protects against malaria. That is the number of malaria in the West African population. It's a gene that was chosen to protect people from malaria. However, it is expected that West Africa will become so warm during this century that it will be too hot for mosquitoes to actually reduce the incidence of malaria. , there are some diseases that make it less likely. But in the end, what they found is that much of what we know is likely to get worse as it rains. and nearly all of the rural United States, especially for those who get their water from wells.

It doesn't matter, it also affects the habitat of disease-carrying mosquitoes and ticks. Here in New England, we have Lyme disease, the most prevalent insect disease in the country. We have undoubtedly seen that disease can live where it [previously] could not live because it is warm enough for mites to survive.

Start here Let's: And we have a short winter to kill it.

Bernstein: That's right.

Start here: Is there a solution here? like what you recommend to people.

Bernstein: Okay, Brad, this is like his $10 trillion question. We are literally at a major fork here. We can sit on our hands and play the fire brigade. So let's wait for all this to happen. We've already seen it and tried to catch up.Right.

So whether it's monkeypox, an animal-to-human disease, you know, we've already had COVID, and he's going to get another coronavirus first. There are plenty of possibilities. You can wait for these things to appear and then hope that you can contain them, but I would argue that we can do better.

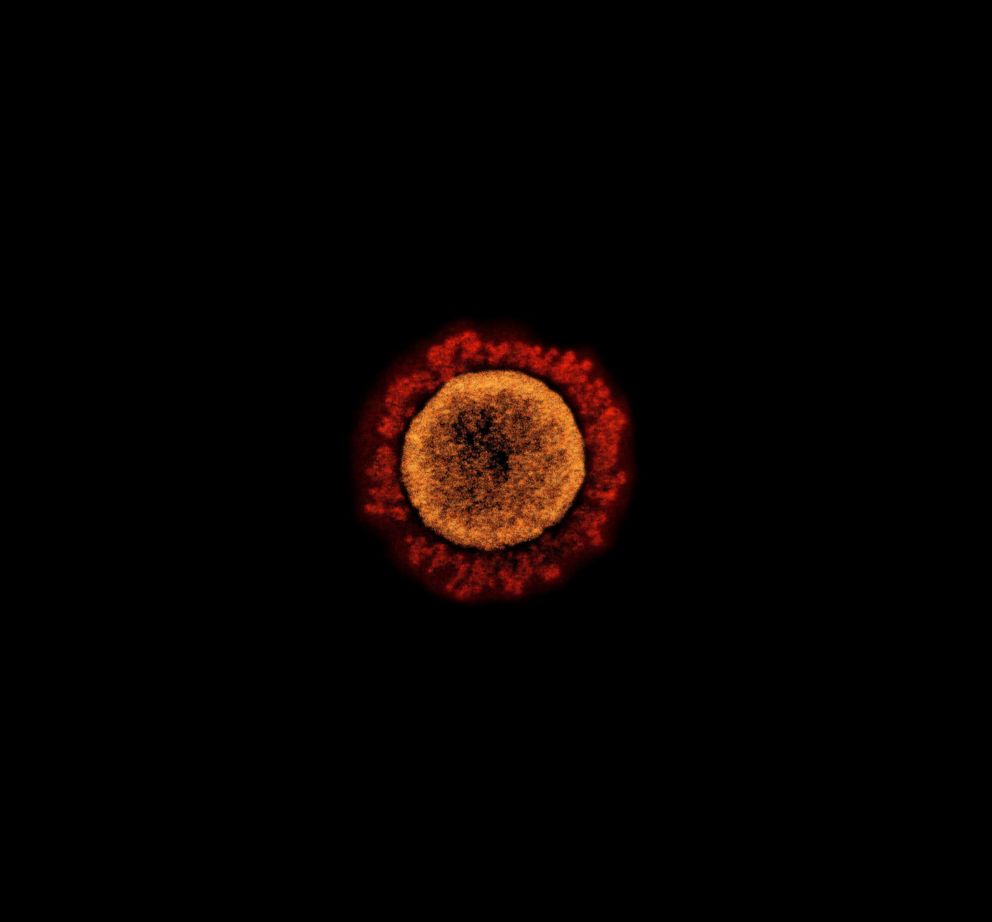

Transmission electron micrographs of SARS-CoV-2 viral particles (UK B.1.1.7 variant), isolated from patient samples and cultured in cell cultures. cultivated in

BSIP/Universal Image Group by Getty Images

These things can be stopped before they actually begin. The initially great and still very important coronavirus vaccine is imperfect at best and only effective against this one coronavirus. So if we can protect bat habitats and protect people from bats, we don't have to worry about making thousands of vaccines.

Poor countries, where these diseases frequently erupt, are the ones least likely to have access to these things first. There are all these elements of fairness that really try to deal with spillovers. There is no doubt that we will always need vaccines, tests and medicines. You can't prevent all disease outbreaks, but you shouldn't do it alone. It would be like trying to address climate change by simply building seawalls and cooling centers, but not the fossil fuels that drive climate change.

Let's start here: Very interesting. all right. It's Dr. Aaron Bernstein of the Harvard Chang School of Public Health, who leads the C-Change program. Thank you very much.

Bernstein: Thank you Brad.