Seven million miles from Earth, a NASA spacecraft crashed head on into a tiny asteroid Monday at a mind-boggling 14,000 mph, the first real-world test of humanity's ability to nudge a threatening body off course before it could crash into Earth.

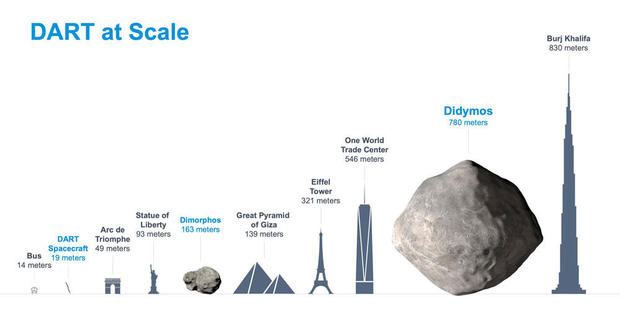

The asteroid in question, a 525-foot-wide body known as Dimorphos, is actually a moon orbiting a 2,500-foot-wide asteroid named Didymos. Neither posed any threat to Earth, either before or after the impact of NASA's 1,260-pound Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART, spacecraft.

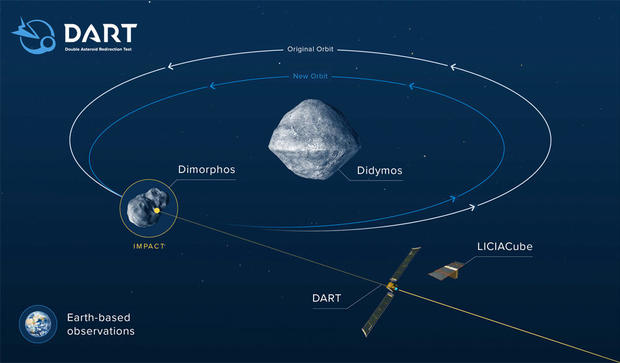

But the double-asteroid system offered an ideal target for the $330-million DART mission because the effects of the probe's impact can be measured from Earth by precisely timing how the moonlet's orbital period around Didymos changes as a result of the collision.

Beaming back images of Dimorphos once per second, the DART probe gave scientists a thrilling on-board view as the spacecraft locked on and raced toward its quarry, spotting it for the first time about an hour before impact when the target was still 15,000 miles away.

Covering the final 1,000 miles in about four minutes, DART's camera showed the target growing larger and larger, from a dim point of light until it filled nearly the entire field of view seconds before impact while traveling 200 times faster than a car on a freeway.

Transmissions ceased at the moment of impact as the spacecraft slammed into Dimorphos, disintegrating on impact and blasting out a fresh crater in the rocky surface. Because the collision happened 7 million miles from Earth, the final few images needed a bit of time to cross the gulf and make it into computers and onto NASA's live stream.

DART: IMPACT! DART has crashed head-on into Dimorphos, hitting it at 14,000 mph and disintegrating as it blasted out a yet-to-be-seen crater; the impact presumably changed the asteroid's orbital velocity slightly as planned, although the exact change will take time to determine

— William Harwood (@cbs_spacenews) September 26, 2022

And at that moment, after years of planning and a 10-month voyage from Earth to the Didymos-Dimorphos system, flight controllers at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory erupted in cheers and applause.

"Oh my goodness, look at that!" someone exclaimed seconds before impact.

"It's amazing guys! Oh my goodness, look at that! Unbelievable!" said Elena Adams, DART mission systems engineer at APL.

"The double asteroid redirection test is a test," said Program Scientist Tom Statler. "We're doing this test when we don't need to, on an asteroid that isn't a danger, just in case we ever DO need to and we discover an asteroid that IS a danger."

A small Italian hitchhiker spacecraft known as LICIACube, released from DART earlier this month, will attempt to photograph the collision and the debris blasted back out into space. Those images will be stored on board and related back to Earth later.

The Didymos-Dimorphos double asteroid system offers an ideal planetary defense test bed because the moonlet's orbit carries it directly in front of and then behind Didymos as viewed from Earth, allowing scientists on Earth to precisely measure slight changes in the combined reflected light from both asteroids.

By timing how the light dims and brightens, researchers have calculated how long it takes Dimorphos to complete one orbit — 11 hours and 55 minutes — and post-impact observations will allow them to determine what effect DART might have had.

Researchers expect the crash to shorten the asteroid's orbital period by about 10 minutes, but it could take a few days to weeks for telescopes around the world and in space, including the Hubble and James Webb space observatories, to make the measurements needed to nail down the number.

"The double asteroid redirection test is a test," said Tom Statler, a DART program scientist. "We're doing this test when we don't need to, on an asteroid that isn't a danger, just in case we ever do need to and we discover an asteroid that is a danger."

He said the DART mission has two primary objectives, the first being a test "of our ability to build an autonomously guided spacecraft that will actually achieve the kinetic impact on the asteroid."

"The second is a test of how the actual asteroid responds to the kinetic impact," he said. "Because at the end of the day, the real question is, how effectively did we move the asteroid, and can this technique of kinetic impact be used in the future if we ever needed to?"

Unlike Hollywood thrillers like "Armageddon" and "Deep Impact," which imagined piloted flights carrying nuclear bombs to deflect or destroy their targets, DART's goal is much simpler and much less destructive.

While nuclear devices might be the last resort in some future Armageddon-class scenario, deflection, not destruction, would still be the goal.

"You just don't want to blow it up, because that doesn't change the direction of all the material," Lindley Johnson, NASA's "planetary defense" officer, told CBS News before DART's launch last November. "It's still coming at you, it's just buckshot instead of a rifle ball."

"What you want to do is just change the speed at which this is all moving by just a bit. Over time, that will change the position of the asteroid and its orbit."

- In:

- Johns Hopkins

- Double Asteroid Redirection Test

- NASA

Bill Harwood has been covering the U.S. space program full-time since 1984, first as Cape Canaveral bureau chief for United Press International and now as a consultant for CBS News. He covered 129 space shuttle missions, every interplanetary flight since Voyager 2's flyby of Neptune and scores of commercial and military launches. Based at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Harwood is a devoted amateur astronomer and co-author of "Comm Check: The Final Flight of Shuttle Columbia."

Thanks for reading CBS NEWS.

Create your free account or log in

for more features.